Romain Polge | Staff Reporter

To show or not to show? This old question has been brought back in the media lately after the release of multiple beheading videos made by the terrorist group ISIS. It would be easy to think that media outlets have agreed on a similar code to deal with this issue, but the reality is different. The debate about the impact and importance of violent images in today’s society is (re)open.

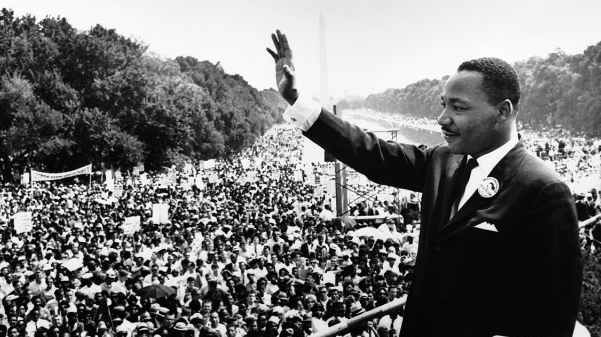

Beheading someone could be easily considered as the ultimate atrocity done to a human being. As Jeff Jacoby points out in his article, Why beheading?, the medium chosen by the terrorist group is not a coincidence. The beheaded videos of James Foley, David Haines and Steven Sotloff were addressed to western countries and media. The same media that depict violence through newscasts, movies, etc., but the beheaded videos are a kind of violent images that westerners are not familiar with, and that’s where the debate starts.

The ethics of showing such images

When it comes to violent images, media outlets have different codes and approaches. The Society of Professional Journalists has its own Code of Ethics, and the first two bullet points of the paragraph, named “Minimize Harm,” are pretty clear on the subject.

- “Balance the public’s need for information against potential harm or discomfort. Pursuit of the news is not a license for arrogance or undue intrusiveness.

- Show compassion for those who may be affected by news coverage. Use heightened sensitivity when dealing with juveniles, victims of sex crimes, and sources or subjects who are inexperienced or unable to give consent. Consider cultural differences in approach and treatment.”

Amanda St. Amand, the continuous news editor for stltoday.com, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch website, explained that the Post-Dispatch “would not publish the ISIS beheading videos under any circumstances.”

“We never considered doing it,” said Amand.

On the subject, the position of the most important newspaper of the St. Louis area seems to be clear. However, when it comes to violent or graphic images, Amand admitted that it wasn’t as easy as it seemed.

“It is something we discuss at length, often on a case-by-case basis,” said Amand.

As the director of the Silha Center for the Study of Media Ethics and Law at the University of Minnesota, Professor Jane E. Kirtley stressed the importance of debating on the subject in the newsrooms.

“I think discussion of this topic is justified because ethical codes are ultimately guidelines, not laws, and each situation requires examination,” said Kirtley.

The impact of violent images

For Kirtley, the real question is not whether media outlets should show the video but “whether the news value outweighs the harm.”

For Andrew Allen Smith, assistant professor at Lindenwood University, specialized in media literacy, viewing the footage wouldn’t “necessarily be more impactful than the knowledge of the videos.”

“Photos and descriptions of the events should be enough information for audiences,” said Smith.

In 2002, the website of the newspaper the Boston Phoenix showed the beheading of Daniel Pearl, a journalist for the Wall Street Journal. At that time, the newspaper was heavily criticized for showing such raw footage, but some people also defended their position.

In Witnesses to an Execution, an opinion piece for thephoenix.com, Dan Kennedy explained why violent images were important. Kennedy had two arguments. First, he believed that like images of the holocaust, the video would truly make people aware of the atrocity; and his second argument was that “they are not qualitatively different from any terrible images that appear in the media whenever some truly awful event takes place.”

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch would never show the videos from ISIS, but they have used images that people could consider offensive.

“We had a lengthy discussion recently before deciding to publish a photo of Michael Brown’s body as it lay on the street in Ferguson shortly after he had been shot,” said Amand. “In that particular instance, the photo was used to illustrate a very detailed story and timeline about why the body remained in the street for four hours after the shooting.”

What is the solution?

Because the situation is so complex, finding a unified solution is impossible. Some news outlets used photographs from the footage, and some provided a link to the raw video.

“If people are truly curious, they will be able to find it their own, no need to necessarily encourage its viewing,” said Smith.

For Kirtley, the intention behind the action matters, and communicating about it is important.

“I do think it is important that news organizations make their own decisions and then share those decisions, and the rationale behind them, with their readers/viewers,” said Kirtley.

The issue that faces news outlets concerning the videos from ISIS brings old but necessary discussions about media violence. What is the meaning of showing the footage? When does violence in the media cross the line from information to sensationalism?

Kirtley knows that there are no defined answers.

“Every case is unique,” she said.