WALKER VAN WEY | Reporter

Reps in the gym strengthen muscles, running improves cardiovascular function and full-contact drills condition the body, but today’s athletes also need to exercise their minds, experts say.

“A lot of what’s going on in your mind affects your body,” said Jennifer Farrell, Lindenwood’s director of student-athlete mental health. “People are starting to see the connection. There has to be some sort of training with the mind to withstand all of the things that are being thrown at athletes.”

According to the American Psychological Association, sports psychology is the “scientific study of the psychological factors that are associated with participation and performance in sport, exercise and other types of physical activity.”

The emergence and use of sports psychologists has picked up steam in recent years, and Lindenwood hired Farrell this year to help meet student athletes’ psychological needs. She said advances in sports psychology became more common in the past decade, after athletes realized that being physically gifted is only half the battle.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”Jennifer Farrell” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Once you get to a certain level, a lot of people are pretty much equal; at that point what really sets people apart is the mental strength. [/perfectpullquote]

Three-time billiards national champion Landon Shuffett said the mental game may be even more crucial in precision sports.

“The game of pool is 90 percent mental, and 10 percent is physical,” Shuffett said. “So that should give you an idea of the level of focus it takes to play the game and all the knowledge that must be learned along with it. The physical aspect, the fundamentals and technique, is a much smaller portion of the skill needed.”

The importance of sports psychology applies to more physical sports as well. Senior football player Bakari Triggs said that the physical nature of football is what makes it so hard on the mind.

“When you do get hit, sometimes you get hit hard, and it takes a lot of mental toughness and courage just to get back up and stay in it,” he said.

Being conscious of the necessary mental strength is a small hurdle. When most athletes realize they’re mentally checked out, conquering the problem may be difficult because it’s not easy to teach yourself how to strengthen and condition your brain.

“One example of our training is visualization,” Farrell said. “Where do you want things to go? It’s all about how you want to program your mind. If you can see things in your mind, there’s a better chance of it happening.”

Besides mental preparation like visualization, sports psychology has various effects on the performance of athletes, including concentration, handling of pressure and stress and recovery from setbacks, according to sportspsychologytoday.com.

In the heat of battle, it’s hard, sometimes impossible, to find time to step back and visualize the rest of the competition. Fortunately, there are also ways to fine-tune your mind on the fly.

“We focus a lot on breathing techniques,” Farrell said. “Another big thing is self-talk. What’re the things you’re saying to yourself in your head?”

Farrell’s services to this point have been on a voluntary basis, but Triggs said that during practices, the ability to maintain mental strength is the focal point of many drills.

“As a team I would say the coach does a great job putting us through rigorous training that will make you rely on mental toughness and also really make you rely on the guy next to you,” Triggs said. “It really shows us that you don’t want to let anybody down, especially the guy next to you.”

Michael Hails, Lindenwood hockey goaltender and sales representative for mental strength coaching company Inner Mind Sports, said that work is already in place to apply sports psychology to athletes before they’re being recruited for collegiate athletics.

“I know that in hockey in Canada, they’re trying to implement it at grade 9 and 10,” he said.

In a short amount of time, the level of talent of the college athlete walking into their freshman season may already supersede most of those leaving in today’s game.

“It will elevate the skill level of the game mentally and physically,” Hails said. “If everyone is learning how to become mentally stronger, they will have to practice more on their physical skill to separate themselves from the rest, potentially creating a whole new level and caliber of superstars.”

Introducing sports psychologists like Farrell to athletes at a younger age may also be a prevention factor. At Lindenwood, three students have committed suicide in the past decade, and all of them were male student athletes, said Dean of Students Shane Williamson.

“We’re just noticing a trend, and so a lot of institutions have started to create a person designated for athletes to treat those students,” she said.

Across the country, suicide by collegiate athletes has begun to rise in recent years, according to insidehighered.com. Collegiate football players alone have a suicide rate of 2.25 players per 100,000.

“[It’s] the pressure,” Williamson said. “Being an athlete, you’re working out, your travel schedule, your game schedule, all your additional commitments are required as an athlete on top of being a student. And they still have families, so what if they have family issues at home, or what if they have to have a job? And so there is a lot of pressure on student athletes today.”

Even while scouting out players, Lindenwood coaches keep in mind there may be outside factors that are bigger than the game.

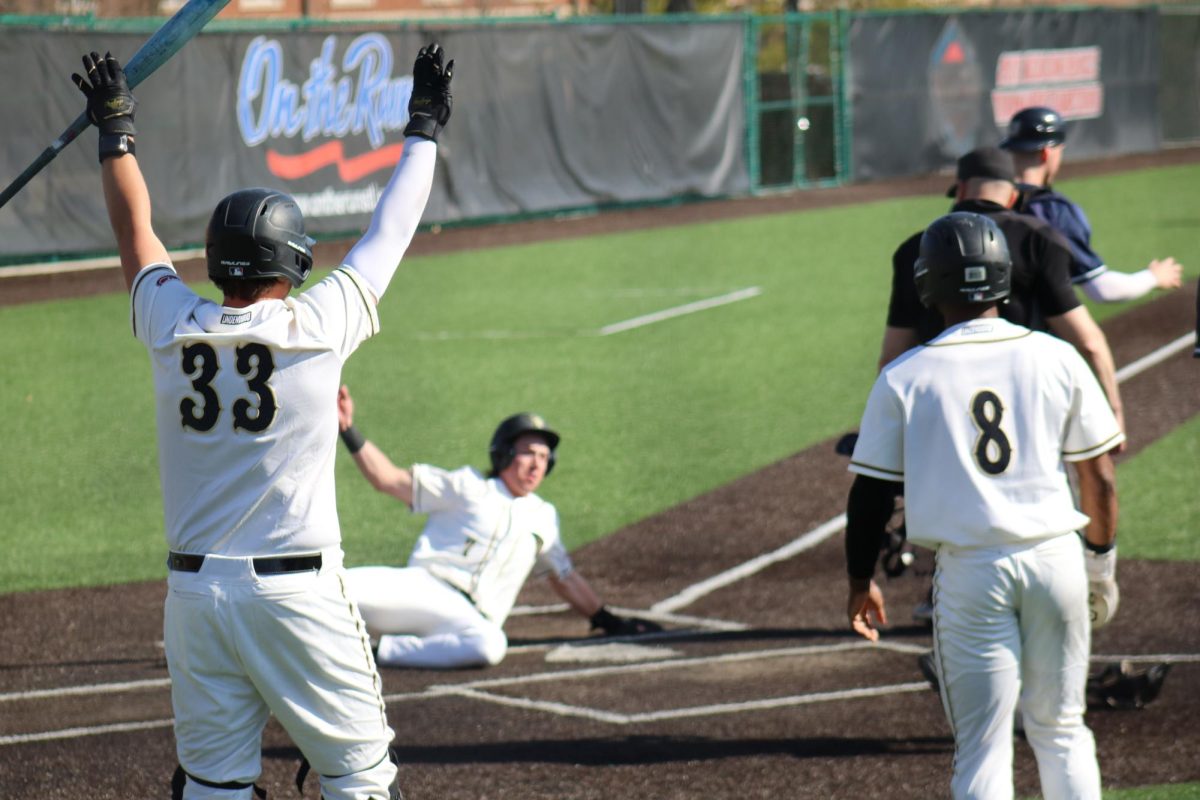

“It’s so challenging because we all break,” baseball coach Doug Bletcher said. “I know I break as a coach. It’s hard for us to know what all is on a kid’s plate.”

Although Lindenwood can’t force student athletes to seek counseling, the school is taking steps to let students know where to go.

“There are posters and cards in team locker rooms and distributed to athletes about mental health, available resources and how to get help or help a friend,” Farrell said. “Overall the department is very committed to supporting students surrounding mental health.”

Boosts in sports psychology and mental strength training from a younger age have already started to show results, Hails said.

“I think it’s the most untapped opportunity that athletes have the access to,” he said. “Science of the brain is getting better. We’re figuring out how to use it to better ourselves; therefore, it’s getting a lot easier to see results when you’re training.”