Raising the curtain on theater waste

The outdoor theater Serenbe Playhouse set out to make the entire set of “The Little Mermaid” out of recycled materials in 2018.

Photo used with permission from Joel Coady

April 25, 2019

This year, Lindenwood University was budgeted to spend nearly $50,000 on theater sets, and after the final curtain call, almost everything will end up in the dumpster.

“Striking,” which refers to the breaking down of a set after the show closes, typically is done in a four-hour window on Sundays or after the curtain call.

The department makes five new sets each year—one for each production. The only set that is reused is for the annual production of “A Christmas Carol.”

Wasting sets isn’t just a Lindenwood problem—it happens at virtually every theater in America, said Academic Production Manager Stacy Blackburn.

While money is a problem at smaller theaters, larger, financially stable theaters do not want to spend the additional time to reuse and reduce.

“The amount of time and energy it would take to break it down into reusable parts is often not worth the labor that it costs to do so,” Southern Illinois University-Carbondale theater professor Thomas Fagerholm said.

Space is an issue with both small and large theaters. It simply is not realistic to store the deck from “All My Sons,” or the awning from “Avenue Q” or the fake rock walls from “The Cripple of Inishmaan”—especially when theaters have new shows every year.

Lindenwood has some storage in the basement of J. Scheidegger Center for the Arts and three 8-by-40-foot shipping containers, but it’s not enough to hold everything.

“Across the board, because theaters can’t afford a lot of storage space, there’s just more waste in our industry,” Blackburn said.

Bradley Branham, program manager for the Southeastern Theatre Conference, said it holds workshops annually in an attempt to solve the problem.

But so far, Blackburn said, “No one has come up with the answer.”

The sustainable challenge

Schools need to build sets—not just reuse them—because of the educational value.

“Students need the experience of designing and taking the sketches and building from that because that’s what they’ll be doing in the real world,” Blackburn said.

After the play is over, it’s not possible to donate sets to local high schools and community theaters because theater sizes aren’t standard; every stage is unique.

“Essentially, scenic designs are often a custom, one-use unit specifically designed or engineered toward the director’s concept for production,” Fagerholm said. “They can be so specific that they become relatively unusable for anything else.”

Lindenwood builds non-truckable sets, which are permanent and not built for breaking down. The only things saved are platforms, some two-by-fours and speciality hardware.

“We pull from the existing stock of platforms, but for the most part, it’s a new set each time,” Blackburn said.

Another potential solution is to donate old sets to organizations like Restore for Habitat for Humanity, that accept used building materials. Restore’s Donation Dispatcher, Cory Naab, said the nonprofit would gladly accept set materials.

But Jason Lively, associate dean for Lindenwood’s School of Arts, Media and Communications, said most of the wood that’s used in theater gets pretty beat up.

“It’s got nails and cleats and hacks in weird places so you can fold it up,” he said.

The dilemma ultimately boils down to limited storage—both professionally and educationally.

In 2018, Lindenwood set designers built a townhouse with stucco finishes and wide stairs, complete with awnings and a fire escape for “Avenue Q,” set in the Blackbox Theater. It was hailed by audience members—and then it was thrown away.

“Where do you store a house?” Lively asked.

‘The Little Mermaid’ as a green platform

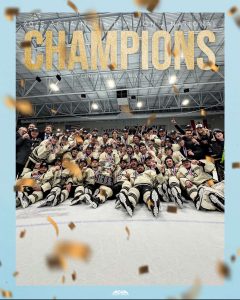

Serenbe Playhouse in Georgia has a reputation for being a pioneer in outdoor theater, but in its 2018 season, it also paved part of the path for greener theater.

The theater rented a 45-foot-long shipping container and created a movement months in advance called “Trash to Treasure.” The community filled the container with recyclables, which the costume and set department turned into “The Little Mermaid.”

“When you’re building something with trash, there are not drawings, like we didn’t have time to look through all our aspects of recycled materials to say ‘Use this one here,’” Joel Coady, production manager for Serenbe Playhouse, said.

Milk jugs were turned into fish heads, bottle caps, tarp and soda cans formed King Triton’s throne, bubble wrap transformed into Ursula’s suckers.

Coady said even though the materials were multiuse, they had to invest time into cleaning and cutting the recyclables to size.

“Nobody cleans out their milk jugs—and they were disgusting,” Coady said.

After the experience, the departments concluded that other elements in theater, like LED lighting, are easier to be sustainable than through materials.

“As much money as we didn’t spend at Home Depot, we probably made that up in labor getting people to crush cans,” Shelby Mays, executive assistant, said.

After “The Little Mermaid” closed, Serenbe loaded back up the 45-foot-long shipping container and sent it to the recycling center. The costumes were donated to local schools.

Despite the labor involved, Coady still said plenty of opportunities exist for innovative theater-makers.

“You don’t need the budgets that I have,” Coady said. “You can do it with being really crafty and really resourceful.”

Innovation starts with education

Some educators have taken a hopeful stance about investigating solutions, and this ingenuity could start in the classroom.

SIUC graduate student Daniel Bennett said he plans to pursue a way to unite sustainability and theater for the rest of his career because he feels it is his responsibility to do so.

“Live performance is such a valuable part of the escape of the real world,” Bennett said.

In Bennett’s experience, he has found the educational realm of theater can turn small budgets into an opportunity, not a limit, to being sustainable.

“We have tools to fix, clean, polish, and we’re also presenting something that is 40 feet away,” Bennett said.

For his graduate set design, Bennett made “Pippin” with a post-apocalyptic feel and partnered with the local recycling center to get TV monitors, lawn chairs and laundry baskets.

Bennett’s professor, Fagerholm, said he finds value in teaching students how to reduce waste.

“Our base material costs can sometimes be cut by a third by reusing previous show materials,” Fagerholm said.

For example, in “Children of Eden,” the designer wanted to use bamboo, but it is expensive to source.

“However, it happens to grow wildly as an invasive species in Illinois,” Fagerholm said. “I found someone locally that had a patch and wanted to get rid of some of it.”

Southern Illinois University-Carbondale’s theater program has half the budget of Lindenwood’s.

Fagerholm said money saved from a set budget can go into shop upgrades at the end of a season and make up for ticket sale losses.

In the past, SIUC has made a giant chandelier from Gatorade bottles and punch bowls. It bought cardboard tubing from a carpet company to make a terra cotta roof and columns.

All in all, Fagerholm said the key is building community relations.

“Don’t be afraid to reach out. All it takes is a phone call or an email to someone to discover a new resource locally that might pay dividends for you.”

Lindenwood senior Costume Design student Melanie Scranton has ambition to make theater respectable because even with the waste, it still serves a purpose.

“It’s not just frills and bows and glitter and bullshit; it’s not,” Scranton said. “It really means a lot to a lot of people, and it’s part of social change or just making someone’s day better.”

As an administrator, Lively said he respects what theater programs pursue.

“I really support the fact that they are giving our students this opportunity to do this professional level of design,” Lively said. “I understand that this costs a lot of money. I understand that repurposing something from a previous show doesn’t give that experience to the students … I’m not thrilled that so much of it goes into waste.”