Your donation will support the student journalists who produce Lindenlink. Your contribution will help to cover our annual website hosting costs.

‘No pain, no gain’ mindset causes student-athletes’ mental health to suffer

May 14, 2020

Sara Wagenknecht dreamed of being a college athlete since she was 10 years old, but when she achieved that dream, she learned that the pressure took a toll.

When she graduated from Fort Zumwalt West High School near St. Charles, Missouri, she was sure Lindenwood was where she wanted to go. But although she was accepted on Lindenwood’s volleyball team, she was not granted a scholarship.

Freshman year, Wagenknecht played only 10 out of 30 matches and feared she wasn’t good enough.

Photo by James Tananan Kamnuedkhun

The following year, she was a defense specialist – a player not assigned a specific position – and played in almost every game. However, Wagenknecht still didn’t have a scholarship, so she decided she needed to put in more work to be noticed by her coaches and earn her place on the team.

“[I was] putting in gym reps, talking to coaches and ensuring that the work I was putting in was getting carried over to the next season,” Wagenknecht said. “I knew I was the best defense specialist on the court, and I just needed to trust myself.”

At the end of her sophomore year, the coaches told her she had earned a scholarship for the following season. Wagenknecht said that was a “big confidence boost,” but halfway through her junior year, she started struggling with the pressure to be perfect. Before she had a scholarship, it felt like she had nothing to lose. Now, Wagenknecht felt like she couldn’t make mistakes or she would risk losing not only her starting position but her scholarship too.

“You realize you are worth more than you thought you were, but now you have to prove that,” Wagenknecht said.

As part of the starting line-up and libero of the team, Wagenknecht started to constantly focus on the things she could do wrong that “would cost points to my team.” She felt the need to be perfect at all times to ensure her position on the court.

Before one match, Wagenknecht’s coaches told her she would play as a right-back instead of a libero for the game.

“I was overthinking and not making the digs I needed to,” Wagenknecht said.

Wagenknecht eventually sought help from Lindenwood’s only student-athlete counselor, Becky Taylor. After working with Taylor and learning different grounding and breathing techniques, along with having better communication with her coaches, Wagenknecht was able to finish out her senior year as the libero and with much less pressure on herself.

However, before she could get help, Wagenknecht said she was put on a waiting list for two to three weeks. Other athletes, she said, had to wait longer.

Lindenwood has 27 sports competing in the NCAA, 24 of which are competing at the Division II level and three for Division I.

Since Lindenwood went fully online because of the pandemic, Taylor said she has been providing counseling services online to follow up with athletes who were receiving counseling in person.

“While there is not currently a waiting list, it is not uncommon for university counseling services to have a waiting list,” Taylor said. “In the event of a waiting list, students experiencing a crisis are seen immediately.”

Although Taylor is the only counselor exclusively for student-athletes, other counselors can help in the meantime.

Taylor said that some of the most frequent concerns are related to anxiety and depression. In counseling, Taylor said she teaches ways to manage stress and relationships.

The invisible threat

From early mornings at the gym to late study nights in the library, student-athletes silently carry the pressure of proving their worth everywhere they go.

Often, the physical side of an athlete takes priority. Coaches rush to get an athletic trainer to have injuries taken care of.

But performing at the collegiate level takes a toll on students mentally, too.

Lillian Marchant, a senior ice hockey player at Lindenwood from California, has had two-and-a-half-hour practices Monday through Friday with three days of mandatory workouts for the four years she played for Lindenwood. The team would compete on the weekends, and during the off-season, workouts are mandatory every day. Marchant said maintaining her school work and personal life was a challenge.

Twenty-one percent of male college athletes and 27% of female college athletes reported that in the last 12 months they have “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function,” according to the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment.

“Student-athletes are held to a very high standard for both school and their respective sports, therefore causing difficulties in life that have to be worked through,” Marchant said. “It is not easy balancing everything and takes a certain type of person to be able to work through the personal struggles to keep going each and every day with all that we do.”

According to a British Journal of Sports Medicine study published in 2019, anger, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue or a change in personality and behavior, might be signs presented by student-athletes struggling with depression.

Although the suicide rate among student-athletes is lower than among other students, over 7% of deaths among NCAA athletes over a nine-year period were from suicide.

Lindenwood Athletics has been no exception to the problem.

On July 28, 2018, Hamilton Marufu, a Lindenwood rugby player from Zimbabwe, died by suicide.

Marufu’s former teammate and now professional rugby player, Nick Feakes, said mental health is a taller hurdle in male sports.

“I think we need to work to get rid of the awkwardness and maybe embarrassment associated with mental health issues in male sports,” Feakes said. “It doesn’t make you any less of a man or an athlete if you’re feeling down, depressed, or anxious.”

Since before Marufu’s death, the Lindenwood men’s rugby team has participated in the Movember #manofmorewords campaign for Suicide Prevention Day each year. The campaign, which has participants sport a moustache all month, strives to help men speak out about mental health.

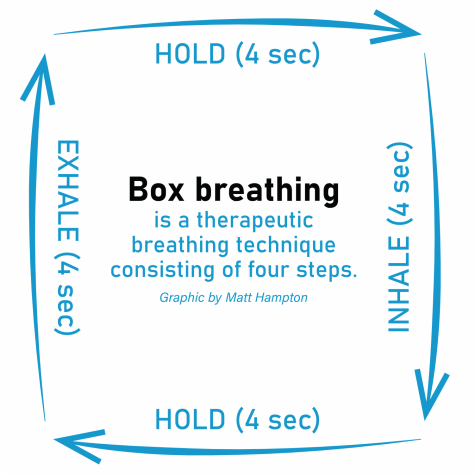

During the season, the team implements techniques that impact both mental and physical health. At half-time, they practice box-breathing, a technique that relieves stress and enhances concentration.

Josh Macy, the head coach of the men’s rugby team, believes that combining mental wellness with physical wellness is paramount for the overall well-being of his players.

“Players with physical injuries see our athletic trainer to recover and then follow through with rehab and additional preparation to guard against repeated injury,” Macy said. “There is no reason the same approach cannot be taken with mental health in an athletic environment.”

Men’s lacrosse head coach Jim Lange said his team has an open-door policy: students can come to his office in the Student-Athlete Center and talk about things other than sports. They are also encouraged to go to counseling.

“It is something that is not frowned upon,” Lange said. “If I am seeing things that maybe worry me or I don’t think I can help with, I will get in contact with our mental health specialist, because [athletes] need someone other than their coach or teammates to have a conversation with.”

The open-door policy was enacted after March 2017, when the lacrosse team lost athlete Isaiah Kozak to suicide.

“That woke us up,” Lange said. “We would think, ‘Man, he would never do something like that,’ so maybe we need to pay more attention to it.”

In order to take care of a roster of over 20 men from 14 states and two Canadian provinces, Lange said the key is relationships.

“It’s getting to know them on a personal level rather than just thinking you are number 22 or number 11,” Lange said.

Kozak’s teammates decided to pay tribute to Kozak by getting permanent matching tattoos.

Seeking Help

The NCAA released a report named “Mental Health Best Practices” in 2016 to help guide institutions on supporting athletes’ mental wellness. The report was created by 25 different mental health organizations, including the American College Health Association.

While the report is not considered NCAA rules, it provides insight on what an institution should be doing to care for their student-athletes. The report covers four main points:

- The student-athlete’s mental health treatment must be provided by a licensed individual who is fully qualified to provide the service.

- The athletics departments are encouraged to coordinate between sports medicine and campus mental health services to develop written non-emergency and emergency plans in situations where an athlete presents mental health-related issues.

- The development of a pre-participation mental health screening of every athlete, as well as a written referral plan prior to a student-athlete’s participation in college athletics.

- The encouragement of athletic departments educating student-athletes, coaches, and faculty athletics to promote a culture of “care-seeking and mental well-being and resilience.”

Currently, Lindenwood Athletics runs a “mental health screen for all incoming student-athletes during their pre-participation exam,” said assistant athletic director Kristin Trotter.

Photo by James Tananan Kamnuedkhun

Taylor, a licensed clinical social worker, works with individual athletes and teams to develop treatment plans, which include setting treatment goals and working to achieve them.

If a student is in a crisis, whether they come to her for help or another staff member reports them to her, Taylor will intervene by working with them to assess their safety and engaging in counseling.

Taylor said that by achieving counseling goals, athletes show improvements in both academic and athletic performance.

For Wagenknecht, attending counseling helped her overcome her anxiety about her sport.

“I went with the mentality of being a badass going into senior year, and ended up rewiring my brain to know that it was okay to have a different position,” she said. “I put in work on the court, in the field house, in myself and I was prepared to handle it. I trusted the process of my efforts.”

But with multiple suicides in recent years, it remains clear that mental health is still an issue for student-athletes.

Mental Health Resources:

Email the Student Counseling and Resource Center (SCRC) at [email protected] or call at 636-949-4541.

Behavioral Health Response (BHR): 314-469-6644 or 1-800-811-4760

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to 741741

Editor’s Note: Nick Feakes is a former Sports Editor for Lindenlink.

This article is part of the Spring 2020 Featured Stories, which were planned for Link magazine before campus closed. For more info and to see the other stories, see here.