J.T BUCHHEIT | Chief Copy Editor

MATT HAMPTON | Reporter

The saga of a former Lindenwood wrestler who was HIV positive and had unprotected sex with dozens of male partners in his dorm room has put Lindenwood at the center of a debate about whether HIV laws are outdated.

Twenty-four states, including Missouri, require people who are HIV positive to tell their partners about their statuses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

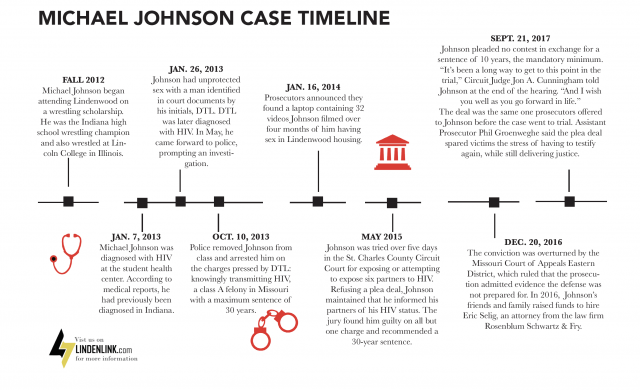

Michael Johnson, a former Lindenwood wrestler, garnered national attention after his arrest in 2013. A St. Charles County judge found him guilty in 2015 of recklessly infecting one sex partner with HIV and risking the infection of four others. He was initially sentenced to 30 years in prison.

“I think getting 30 years for that is way too harsh,” said Filip Cukovic, one of Johnson’s partners. “I mean there are people who are charged for rape who get significantly less than that.”

The story generated headlines in publications such as The Nation, in part because of graphic details of Johnson’s sex life. He met sex partners on hookup apps such as Jack’d and Grindr and often posted photos of his athletic torso on other social media sites on which he used the name “Tiger Mandingo,” according to testimony at the trial.

The case also ignited criticism about the length of the sentence, with some saying it was motivated by racial and homophobic prejudices.

Johnson appealed his case and was awarded a new trial. He later agreed to a deal with prosecutors.

On Sept. 21, Johnson pleaded no contest to the charges and was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Many used Johnson’s case to condemn Missouri’s HIV disclosure laws, which were enacted in 1988 during the peak of the AIDS scare.

Critics argue that the laws promote HIV stigma and discourage getting tested. The American Psychiatric Association released an article citing Johnson’s long sentence and the advancements in AIDS treatments as evidence against disclosure

laws.

Sean Strub is the executive director of the SERO Project, a U.S.-based national network of people living with HIV “fighting for freedom from stigma, discrimination and criminalization.”

He said that making HIV transmission a criminal offense, in the absence of a malicious intent to harm, is “a horrible public health policy and is making the epidemic worse.”

Strub said the laws that mandate disclosing one’s HIV-positive status do more harm than good.

“HIV statutes may have been passed with good intention — to reduce HIV transmission — but there is zero evidence they have done anything toward that goal,” he said. “And a growing body of evidence points to the criminalization statutes doing the reverse: making the epidemic worse by discouraging people from getting tested or accessing treatment and making disclosure more risky and more difficult.”

Brryan Jackson, whose father knowingly injected him with HIV in an attempt to murder him, now speaks out about HIV infections. He believes the court did its job in sentencing Johnson, but also said people with these infections need more information on treatment.

“There were people who were affected by this, and that’s the accountability people need to be held to, not just with HIV, but with any infectious disease,” Jackson said. “And the people who have the infectious disease need to get more information to protect themselves and the people around them.”

Otha Myles, a specialist on infectious diseases at St. Luke’s Hospital in St. Louis, testified against Johnson in his 2015 trial. Myles focused his comments on the victims and said while HIV treatment has improved, HIV medications contain side effects, and those afflicted must remain on the medications for life. He also said problems often arise when people stop taking their medications.

Many people are reluctant to undergo tests for HIV because of the repercussions that a positive status would provide, including being forced to tell a prospective sexual partner about having HIV, said Tony Rothert, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union.

“It’s not very romantic to pull out a release form asking someone to sign acknowledging that they’ve been told,” Rothert said. “It’s not conducive to having sex to ask someone on video that they understand and consent that you have HIV.”

“It’s not very romantic to pull out a release form asking someone to sign acknowledging that they’ve been told,” Rothert said. “It’s not conducive to having sex to ask someone on video that they understand and consent that you have HIV.”

Rothert said another reason people feel discouraged from being tested is because people cannot be found guilty if they were unaware that they were HIV positive.

However, Cukovic, who is HIV negative, said he believes people are not getting tested for another reason..

“[Many people] decided not to get tested just because they would prefer not to know, not to know at all, and not because it might have some legal implications, but because it might have very personal psychological implications,” he said.

St. Charles County Prosecutor Tim Lohmar, whose office prosecuted Johnson, said the penalties for the crime probably are too harsh, but he has to enforce the laws of the state.

“Typically with these criminal laws like this, I tend to take the approach that the legislature is the one who can vet the laws and get the pros and the cons, and when they do that, that’s my directive is to follow whatever it is,” he said.

While Johnson was sentenced to serve 10 years in prison, he may be only be behind bars a few more months because of time already served and parole guidelines.