ESSI AUGUSTE VIRTANEN & KYLE RAINEY| Editors

Adjunct professors have become the backbone of the higher education system in the United States — and at Lindenwood.

In 1975, 30 percent of college faculty were adjuncts and by 2015, the number had increased to 48 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

In turn, the number of full time professors in the country has dropped more than 25 percent in the last 50 years.

At Lindenwood, 803 adjunct instructors are teaching this semester in addition to 292 full-time faculty, according to Deb Ayres, the vice president of Human Resources. This means 73 percent of faculty at Lindenwood are adjuncts.

As part-time positions appear to be replacing more full-time positions, many who want to build careers in the classroom are forced to work two or more adjunct positions, or to find other forms of employment elsewhere.

Sciences adjunct professor Yvonne Cole teaches at two other universities in addition to Lindenwood. As a retired high school teacher, she said she teaches simply because she wants to, not because she needs the income.

“I’m an adjunct because I want to be, but this is not my sole source of income,” Cole said. “The frustration I see among some of the younger adjuncts is you have people who have the qualifications to be full-time with Ph.D’s, yet they’re not being hired.”

She said she has no complaints about working at Lindenwood, but acknowledges it can be inconvenient.

“It’s fine; the only thing that can happen sometimes is if you get displaced from a class because a full-time person wants it, that’s the nature of being an adjunct,” Cole said. “As an adjunct, you are by definition a part-time person.”

Adjunct professors are part-time faculty members who can teach generally two or three classes per semester, said Stephanie Afful, associate professor in psychology and the president of Faculty Council.

Across the country, adjunct professors have begun demanding more from universities because they say their compensation is unfair.

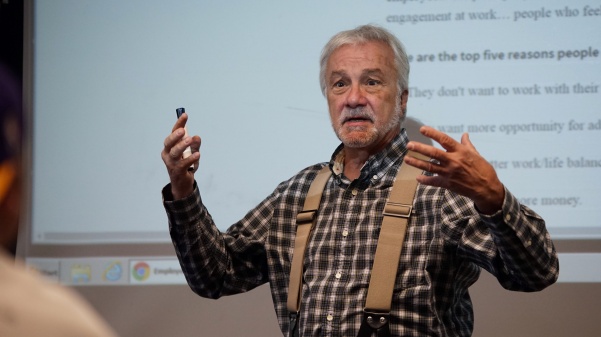

Kim William Gordon, a former communications professor, stopped teaching at Lindenwood in late October. Before leaving, he said he was not planning to come back next semester because of unfair working conditions.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”Yvonne Cole” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”The frustration I see among some of the younger adjuncts is you have people who have the qualifications to be full-time with Ph.D’s, yet they’re not being hired.”[/perfectpullquote]

“I have some very humanitarian interests in being in a classroom,” he said. “I’m also here because I need to pay bills; I need to eat.”

Afful said the problem is a system problem and goes beyond Lindenwood.

“I don’t think adjuncts are upset with Lindenwood,” Afful said. “I think they’re upset with the system. I mean I don’t think we are doing anything per se to disadvantage. It’s just about competition and kind of the market out there.”

Afful has worked as an adjunct at four local universities and said she understands the systematic disadvantage of being part-time.

“You’re doing the same amount of work for significantly less pay, and the biggest issue is that there are no benefits,” she said. “So we rely on our adjuncts for a lot of our courses, as do almost all universities because it costs less. It is an economic decision.”

CONTRACTS AND PAY

Debra Leigh Scott has been working on a documentary focusing on the treatment of adjunct instructors called “’Junct: The Trashing of Higher Ed. in America.”

She taught as an adjunct instructor on and off for 20 years in the Philadelphia area, but quit this past summer because teaching circumstances weren’t getting any better.

“What I’ve found is that any university, no matter how wealthy it is, will pay as little to its adjuncts as it can get away with,” she said. “I don’t think that wealth [of the university] translates always into better pay for the contingent faculty, which is always [the] majority [of] faculty.”

Ayres said that adjunct pay at Lindenwood comes down to four factors: time spent at the university, academic credentials of instructors, course level and the subject matter being taught.

According to a Fall 2017 adjunct contract, the number of courses instructors can teach are limited to make sure adjunct teachers remain part-time, or working fewer than 28 hours a week.

Ayres said adjuncts are paid between $2,500 and $5,250 per semester.

If fewer than seven students enroll for a course, teachers may be paid 1/7 original pay per student or their course may be cancelled.

Afful said the Faculty Council conducted research that compared Lindenwood to other colleges, and of those who responded to the survey, Lindenwood pays higher. Afful could not provide the specifics of the research.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”Yvonne Cole” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”As an adjunct, you are by definition a part-time person.”[/perfectpullquote]

“We can say on the record we pay competitively, and in some studies we actually pay more than some of the other competitors,” Afful said.

She said adjuncts should be paid more but the university needs to be realistic about its budget.

Afful said in an email that adjuncts receive their official contracts two weeks before the term but “that it may differ based on the school. Some schools issue more in advance.”

Adjunct professors Gary Corbin and Rebecca Williams teach in the school of sciences at Lindenwood. They both said they are content teaching at Lindenwood, but the time they receive their contracts varies greatly. Corbin said he has gotten his contract on the first day of classes on a few occasions.

Afful said, “It is unfortunate when we have to let an adjunct know last minute that a class didn’t make [it], but that’s not because of ill intent or disrespect; it’s because the students enroll late.”

UNIONIZING

In recent years, some adjunct instructors have begun turning to unions in search of better working conditions.

Efforts to unionize were attempted at Lindenwood around 2014. Instructors were eventually met with a series of documents from university officials urging teachers to stay away from unions. They warned of union fees, poor representation and potential pay cuts.

In 2016, adjunct instructors at Washington University unionized, and their agreement with the school promised things like a $250 cancellation fee if a course is dropped within seven days of a scheduled class.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”Stephanie Afful” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“In some cases people were actually paid less after they unionized.”[/perfectpullquote]

However, things like health care and tuition benefits remained unchanged, and now all adjuncts at the university must either pay dues in the amount of 2.5 percent of their pay, pay non-member fees, or make donations in the same amount to a scholarship fund.

Afful, who was an adjunct at Washington University at the time, said it worked for the university but was not easy.

“In some cases people were actually paid less after they unionized,” she said. “Because now their pay scale is regulated in a way that it wasn’t before, so sometimes that can be a disadvantage.”

While working on her documentary, Scott has come to the conclusion that current unions aren’t the solution.

“You can’t handle a national problem by having a piecemeal kind of unionization at one university at a time, because it’s taking decades to unionize,” Scott said.

VALUING PART-TIME FACULTY

Ayres said in an email that two human resources employees are dedicated to work with adjuncts to improve their work conditions.

She also said the university used feedback from adjuncts to help decide the four major factors that determine adjunct professors’ pay at Lindenwood.

“As a result, compensation for adjunct instructors was restructured to reflect that criteria,” Ayres said.

Afful said adjuncts at Lindenwood also get two free meals a week to help compensate them for their work.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”Gary Corbin” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”We have office hours and truthfully, in my case, … I’ve had one, two, three students come by for help all term. In most cases we have space for that.”[/perfectpullquote]

Additionally, reserved free parking and designated office spaces in the Library and Academic Resources Center have been added because of adjunct requests.

This was done to secure parking and “a quiet place to plan, grade or meet with students for advisement.”

Corbin shares an office with several adjuncts in Young Hall. He said students don’t come by often during office hours.

“We have office hours and truthfully, in my case, … I’ve had one, two, three students come by for help all term,” he said. “In most cases we have space for that.”

Cole said teaching at college has given her freedom in the classroom and that she’s OK with the shared office space and commutes between schools associated with adjuncting.

“When you sign on, you are signing on for that,” she said. “But because you’re finding so many of the people who are adjuncts would like to be full-time so they can support their families, it is very frustrating for them.”

Afful said Lindenwood is always looking for more ways to support adjuncts.

“If there [are] non-monetary ways that we can help and support adjuncts, we want to know that,” she said. “We don’t have money to dispose, but if there are other ways that we can help support adjuncts, we want to do that.”

Clarification: A version of this article published in the November 2017 edition of Legacy Magazine included information that may have misled some readers. The article included four paragraphs that referred to comments from former Lindenwood adjunct instructor Kim William Gordon regarding his adjunct pay in 2016 and how that might be used to calculate an hourly wage. Those paragraphs have been removed in response to an explanation from Vice President of Human Resources Deb Ayres, who said that guidelines included in 2017 adjunct contracts limit the number of courses an adjunct instructor can teach, as to keep their total hours of work under 28 hours per week.