KAYLA DRAKE | Host

MATT HAMPTON | Producer

This is the second episode in a four-episode documentary podcast series about Dennis C. Spellmann, president of Lindenwood from 1989-2006. Click here for the previous episode, and here for the next installment. A transcript of the episode is below. A list of sources is here.

Kayla Drake: Love him or hate him, Spellmann quickly brought Lindenwood back from the brink of closing. Not only that, he purchased the land that is now the new side of campus, student housing, and the shopping center across the street. He embarked on building projects which transformed the area.

Some have hailed Spellmann as a business genius, but not everyone was happy with the way he ran things, whether it be the residents whose homes he bought up for student housing, or faculty who disagreed with his business-like approach to Lindenwood.

Dr. Michael Mason is a religion professor who’s been at Lindenwood since 1991. And despite disagreeing with Spellmann – Mason can’t help but respect what he did.

The Rev. Dr. Michael Mason: I mean, basically there were 800 students when he came in here, and all these empty buildings that were falling down and in 10 years he turned it around. We were out of debt, our buildings were paid for, new ones were being put up. You know, what can you say? A lot of times I disagreed with the way he did it, but I understood what he was doing. I had the advantage of being close enough to him to know what he was thinking about and talking about, and I think a lot of other people didn’t.

Images from Google Earth

Gif by Matt Hampton

KD: If you look at a map of the area before Spellmann, it is almost unrecognizable.

Professor Hollis C. Heyn: What is now Harmon Hall was the fine arts department and all those parking lots didn’t exist. There were tennis courts there, and a field hockey field.

KD: That’s Hollis Heyn, who graduated from Lindenwood in 1975 and is now an English professor.

HH: And from that, just kind of rolling pastoral bucolic landscape. Where you see Evans and the Hyland Center, all that was kind of an open field with trees.

KD: Where the Scheidegger Center is today was a drive-in theater, and businesses lined First Capitol. Behind them was a dilapidated trailer park which would become another point of controversy for Spellmann’s critics. Spellmann later moved students into these trailers before the eight identical brick dorms on the horizon side were built.

MM: First time I rode through there, I thought I’d gone into a horror movie because of garbage, and dogs on top of dog houses and basically he bought those up, put students in them, advertised them over three to five years, turned around and sold the trailers off for more than he bought them for and, you know, invested in the first dormitories.

KD: Spellmann conducted extensive renovations. Before he came, the library was sparse, and many of the buildings were out of date.

MM: If you went into Ayres, the contractors came in there and they had three months in the summer, and you could actually go upstairs in Ayres and look down through the floors and see almost all the way the basement. So they had to come in and replace the floors. They had to put up I don’t know how many million square feet of drywall in there.

KD: Spellmann had big plans to transform Lindenwood and the area around it – even beyond what he accomplished in his lifetime. On campus, he built the Hyland Arena, six new dorms, and his namesake the Spellmann Center – which still functions as a central point in Campus life. Residential students rarely pass a day without going through the building.

But According to Christie Rodgers, who worked during the Spellmann years and is now the VP of Student and Academic Support Services, along West Clay and First Capitol, businesses were decrepit, but the owners wouldn’t sell the land.

Dr. Christie Rodgers: It became a major eyesore for St. Charles. And so he knew that that wasn’t going to fly with potential families coming in as well, and so he started his approach to make sure he was going to start buying up that property.

KD: It needed a negotiator like Spellmann to close the deal.

Matt Hampton: But of course, there was one spot on the monopoly board he couldn’t get.

KD: That’s our producer, Matt Hampton. Autozone refused to sell, multiple times. Still to this day is nestled in between Blanton Hall and First Capitol. Autozone is the first thing people see coming to campus off Highway 70, almost functioning as a welcome sign of sorts.

Image from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

On the other hand, much of the surrounding area was residential neighborhoods, including what is now student housing and the shopping center across the street. Residents sold to Lindenwood for less than they would have liked, because they feared property values would drop as students moved into the neighborhood.

MH: When Spellmann bought up this land, some people protested having students move in next to them or being pushed out of their home or business.

CR: He wasn’t going in the community and shaking hands. He was trying to make things happen and happen right now. So he was just doing as he thought was best without really a whole lot of insight or opinion from the surrounding community.

MH: Mass Communications Professor Rich Reighard lived in the area and has worked at Lindenwood since 1987.

Professor Richard Reighard: Some people liked it, I mean it’s like, hey, ho, wow, we finally have a you know, a new Schnucks and all this stuff. But, but yeah, speaking as a St. Charles resident because I live a few blocks over from the college and it was like yeah, there were a whole lot of people weren’t overly fond of the growth of Lindenwood, because it seemed like they were taking over the middle of the town, and to a large part he was.

KD: Students who lived in the trailers Spellmann bought liked having more independence from the conservative culture of the dorms, but it came at a cost. The trailers fell into disrepair, and some called it “Dogpatch” or “the cockroach pit.”

RR: He probably held on to the trailer park longer than he should have, so that’s where you get the stories of, you know, students being housed in trailers where the floor was falling out, and there was no heat or running water.

KD: By the end of 1990, Lindenwood had a fully funded $1.6 million endowment.

And when Spellmann died in 2006, it was over $50 million.

So how was he able to turn it around from the verge of closing?

For one thing, he cut the number of staff by two-thirds: from 427 to 140.

RR: We had more employees here than we had resident students. That’s no way to run a railroad.

MH: Besides reducing security, maintenance, and administrative staff and part-time faculty, Spellmann trimmed expenses by $2 million overall. He cut the yearbook to save money, and he was said to go around at night to make sure people didn’t leave lights on. He also negotiated new deals for Lindenwood.

RR: Most banks around here wouldn’t touch us because it was like “We’ll just waste the money or blow through it like crazy,” but he got four times as much money as the college had ever asked for from the banks by personally guaranteeing it. So, suddenly we were flush with cash and he started to change things.

KD: Under Spellmann, Lindenwood did not just become a university, it became the fastest-growing university in Missouri in the early 2000’s.

In 1989, Lindenwood had under 3000 total students, but within 10 years, that number tripled, and in 2006 it was over 14,000. It was the Spellmann enrollment boom.

One of those students was Chad Briesacher, who graduated in 2008.

Professor Chad Briesacher: We were growing so fast at the time, the university, they couldn’t keep up with housing. At the start of the semester, there were people on cots in the dorm lounges and things because he would overbook the university. Whether that was him or not, people would be like, “Oh, President Spellmann is the reason we’re doing this.” Whether that was true or not, we didn’t really know, but it’s easiest to blame the guy on top.

KD: Spellmann thought it was a crime to see an empty bed (or even if they weren’t really beds). So, he thought of outside-the-box ways to get students enrolled. One of those strategies was pork for tuition. This concept was so bizarre that it attracted national news organizations.

MH: Outlets from The Today Show to the BBC to the LA times ran with the story of Lindenwood’s pork for tuition program. This is from a 2002 NPR interview with Spellmann.

NPR Anchor: “Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Missouri, has a novel way of collecting tuition. Instead of taking checks or credit cards, Lindenwood takes hogs. Students can barter pork for pearls of wisdom from Lindenwood professors. Some half-dozen students have gone through school this way in the past few years.”

KD: Starting in 2000, Spellmann bought pigs from local farmers above market value in exchange for a reduction in tuition. Then, Lindenwood paid to process the meat, which was used in the Ayres cafeteria for bacon, sausage, and more. Spellmann’s motive was that by doing this, he could both save on food costs and draw in more students.

NPR: “So who came up with the idea of bartering hogs for tuition?

Dennis Spellmann: “We did, because we read the price of hogs a couple of years ago got down to $8 a hundred, so at $8 a hundred it would be about $25 per hog, and yet we were still paying the same price for ham and bacon and sausage and ribs, so we decided to cut out the middleman and help the farmers’ kids go to college.”

KD: Always the savvy businessman, working angles and drawing inspiration from his farming upbringing, he even advertised in farm journals with the headline “Pork: the other tuition payment.”

DS: “Generally, at most meals you can eat high on the hog, if you’re getting them fresh.”

NPR: (chuckles) “I guess you’ve had a while to practice these jokes, Dr. Spellmann.”

DS: “We get a lot of jokes about this, but the kids really have eaten well in our cafeteria.”

MH: Glen Cerny, a former KCLC director, still remembers the attention about Spellmann’s creative use of bartering

Glen Cerny: Did anybody care if the tuition was paid in Euros or in dollars or in pesos or in pork? He didn’t. And I mean it was much more of a sense of humor thing for him “Hey look, talk to us. Do you don’t think you can go to college? Talk to us have our recruiters sit down with you and let’s see what we might be able to do.”

KD: Well, some people did have a problem with him taking tuition in pork. PETA, staged a protest on campus and wrote to Spellmann asking him to stop accepting “tortured pig carcasses.” But Spellmann, unbothered, shrugged off the protest, and the program grew to include cattle and other livestock.

Spellmann not only increased enrollment through pork and learn, he also made aggressive use of work and learn. Besides giving students a way to pay for tuition, Spellmann believed it gave students “hands-on responsibility” and a “sense of kinship with the school”. He even let parents work on campus for their children’s tuition. In 2006, about 85 percent of students at Lindenwood took part in work and learn.

MH: This is Debbie Nicolai, a Mass Communications professor who has worked at Lindenwood since 1993

Professor Debbie Nicolai: You could be anything, from KCLC, you could be grounds you could be maintenance, you could be working in the cafeteria, business office, you know, they were all kinds of jobs if you wanted at a job. And it was really beneficial for international students, because they would come here and they would get help with their tuition, because they would get that work and learn.

KD: The student worker program has since been significantly downsized, but international and American students still take advantage of those jobs – if they can get them.

Now there was a significant community of foreign students at Lindenwood before Spellmann came, but he took it a step up and increased recruitment overseas.

Richard Reighard: There was a source of income there, of these students, and many of them attending college on grants from their home governments to come to the United States and get a U.S. degree, so we tapped into that market. For the most part, that worked well, although, at some point, when you run into students who don’t speak English, that’s a problem.

MH: That’s professor Reighard again. The language barrier sometimes caused problems during the large influx of international students.

RR: That’s always the constant battle on the academic side vs. the business side. The recruiting office wants to bring in as many students as they can, so they’re like,”Well, they’re OK on English,” and when you get them in class, and they’re like “Hello, professor” “Hi, what’s your name?” “Hello, professor.” They don’t speak English. “Oh, boy.” There were always problems, but yeah, he did a lot of aggressive overseas recruiting.

KD: In 1997, the first lady of Panama visited Lindenwood after Spellmann signed an agreement with the country to send its students to Lindenwood rather than to Cuba. To this very day, Panamanians form one of the largest segments of the international population at Lindenwood.

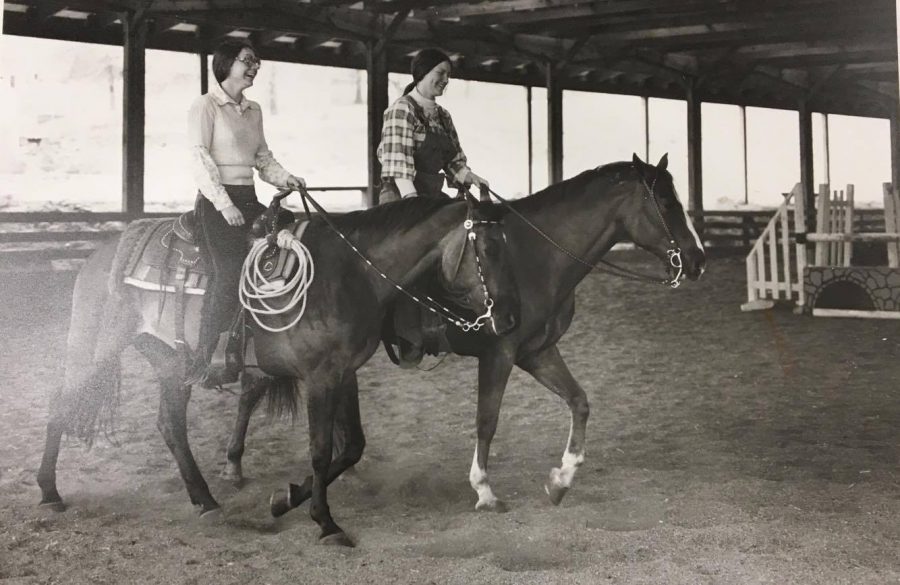

Photo from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

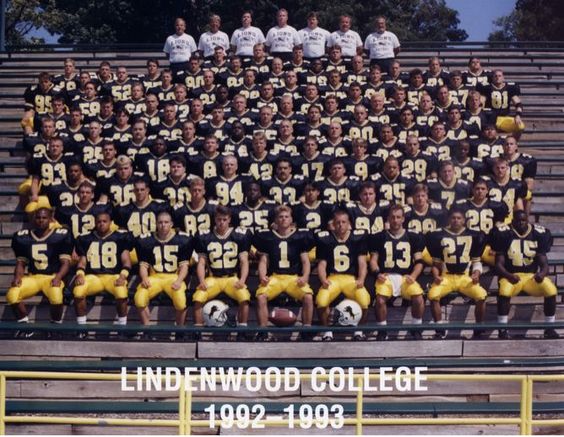

However, the main plank of Lindenwood’s strategy was sports.

Spellmann, himself a college football player, created the college’s first football team in 1989, and enrolled a massive recruiting class with over 100 fresh-faced players.

MH: Cerny was the faculty athletic representative at the time.

Glen Cerny: He saw that there was no college football team in the St. Louis market. So could he create a college market for football in St. Louis? There were other teams, but nobody was great, you know. And that would bring people to the campus, it would raise the visibility of the campus, and he brought in a ton of kids.

MH: Lindenwood got a renovated football stadium and new athletic facilities, and the number of sports offered grew from seven to thirty under Spellmann.

GC: From my perspective – but I’m guessing it’s pretty accurate – the whole point of athletics was to increase enrollment. He would discount everything. I heard him say multiple times, you know, if you recruit the high school football player, well, his girlfriend will probably come with him.

KD: Lindenwood teams dominated in the NAIA, winning a total of 128 conference titles. The prestige of an athletic scholarship brought new students in, even those who had minimal sports experience, and they kept their scholarship to Lindenwood even if they decided to leave the team – a deal which only ended in the last few years.

GC: His standard line was “The airline knows how many seats they have on the plane, and their job is to fill them as best they can. We have beds here, and we need to make sure those beds are filled,” which again, alarmed a lot of the academic community. Are we lowering our academic standards? What are we doing here? Dennis’s position was we’ve got to fill beds. We’ve got to drive revenue.

KD: Though sports attracted many new students, Spellmann’s hungry culture to bring in student-athletes caused some to worry that the enrollees were low-quality.

GC: I took a lot of this crap personally because one of the kids that was recruited to play soccer at Lindenwood was a kid by the name of Christopher Cerny and his dad could have been a slime bag but his mother is one of the kindest, honest, most beautiful people God ever created. So I took exception – there was a great broad brush by some on the campus community that these kids were all marginal, and that’s simply not true. Now, were there some that were ehh? You bet. But I can guarantee you that on my time as faculty athletic rep, there was not a single kid that came in that did not meet NAIA requirements, period.

KD: Despite fears of falling academic quality at LC, the numbers show that the average test scores of incoming freshmen did not substantially fall

So, that was Spellmann’s business mentality. It was what kept Lindenwoood afloat, but there’s no denying people disliked his tactics.

Tune in to the next episode to find out what it was like to be a student under his rule.

MH: He was known for his strict discipline, and his policies were met with criticism from faculty too – especially when he cut tenure.

GC: Oh, all hell broke loose, very, very quickly. One of the early, early steps was to wipe out all tenure.

MH: How was he viewed by faculty and staff at Lindenwood in response to him getting rid of tenure?

GC: Oh, pure hatred.