How Lindenwood handled the Spanish flu of 1918

Photo by Tyler Keohane

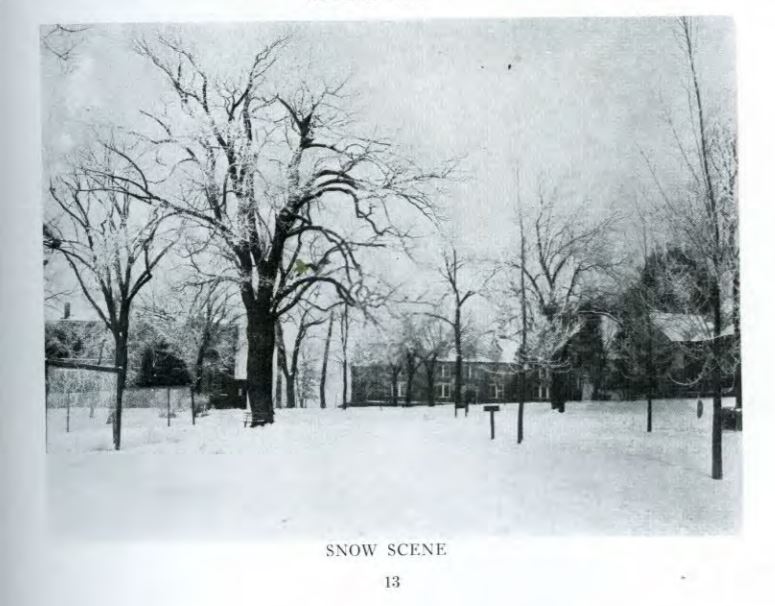

Photo of Lindenwood University in the winter of 1918.

Taken from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

March 27, 2020

Correction: A previous version of this story said there were no Lindenwood-related Spanish flu deaths. One professor died from the pandemic.

Right now, Lindenwood University is facing tough decisions about the coronavirus pandemic, but just over 100 years ago, the college was in a similar situation.

In 1918, a pandemic known as the Spanish flu swept the globe, killing an estimated 50 million people.

However, only 60 of Lindenwood’s 287 students became ill, Paul Huffman, the Lindenwood archivist said. No students died from the Spanish flu, although a professor died from it in 1920.

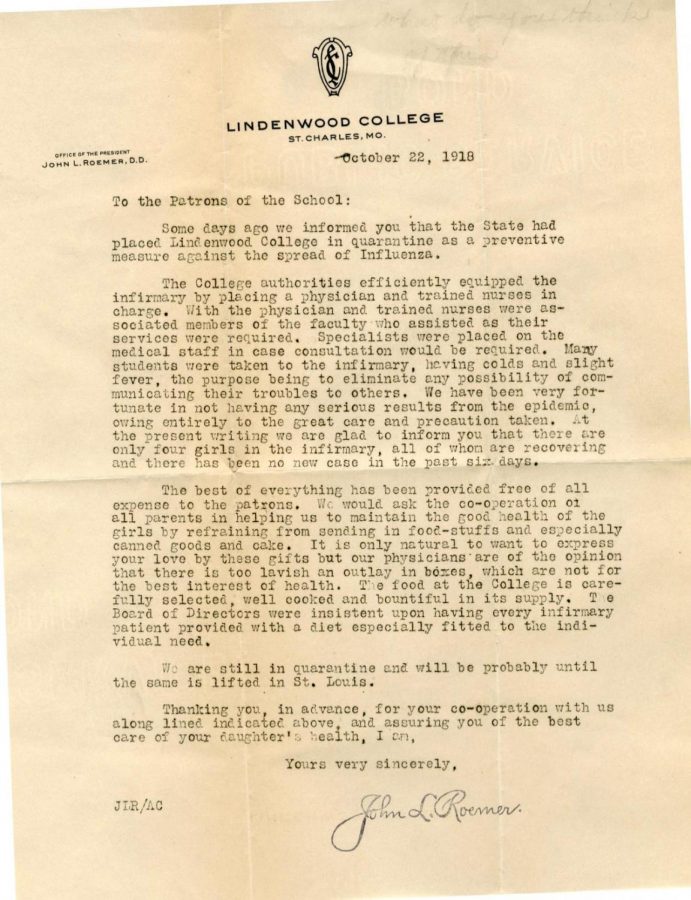

This, in part, was due to the quarantine the state of Missouri placed on campus in October 1918.

In a letter to the school’s patrons after the quarantine took effect, Lindenwood’s president, John L. Roemer, said, “We have been very fortunate in not having any serious results from the epidemic, owing entirely to the great care and precaution taken.”

According to the letter, potentially infected students were placed in an infirmary, staffed by a physician, nurses, and “associated members of the faculty.” Huffman said it is not known where the infirmary was located.

“Many students were taken to the infirmary, having colds and slight fever, the purpose being to eliminate any possibility of [spreading] their troubles to others,” Roemer’s letter said.

Roemer also asked parents not to mail food or packages to students to stop the spread of the Spanish flu.

In an email to students about the coronavirus on Friday, president John R. Porter referred to Lindenwood’s handling of the Spanish flu, saying, “We see that same spirit of cooperation and drive during the current crisis.”

Like the coronavirus pandemic, the Spanish flu caused schools to suspend session, businesses to close, and churches to stop their Sunday services in St. Louis. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that St. Louis was one of the very few cities to actually order a city-wide lockdown. Theater companies, musicians and performers protested the lockdown saying it “threatened their careers.”

The Spanish flu hit mildly in the spring of 1918, then a deadlier wave swept the U.S. the following fall causing victims’ skin to turn blue and their lungs to fill up with liquid. However, St. Louis was prepared for the second wave due to it hitting the East Coast cities first, according to the Post-Dispatch.

The lockdown in St. Louis lasted from early October to late December, after Christmas. According to the Post-Dispatch, St. Louis had the lowest death rate of the top 10 largest cities in the U.S., which was credited to the quarantining of the city.

Philadelphia, which did not go into quarantine, experienced nearly twice the death rate within the same time frame.

The Spanish flu was transmitted via “respiratory droplets,” the same way the new coronavirus is transmitted, according to Julia Ries, a reporter for Healthline. Symptoms included fever, chills, and fatigue. And like in 1918, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend social distancing to stop the spread of COVID-19 because of its proven effects of slowing the spread of an easily-contractable virus.

To stay up-to-date on news regarding COVID-19 at Lindenwood and in the St. Charles area, check Lindenlink.com’s “COVID-19” section under the “news” category.