KAYLA DRAKE | Host

MATT HAMPTON | Producer

This is the first episode in a four-episode documentary podcast series about Dennis C. Spellmann, president of Lindenwood from 1989-2006. Click here for the next episode. A transcript of this episode is below. A list of sources is here.

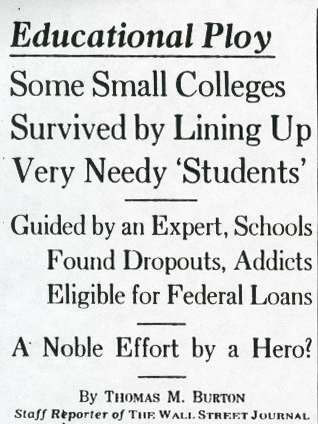

CORRECTION: This podcast mentions an article in the Wall Street Journal about Spellmann’s work at other colleges. It was not a front-page article as the episode stated.

Kayla Drake: In 2019, Lindenwood University is a private, four-year liberal arts school with about 9,000 students. It has a historic campus in St. Charles, Missouri, which is 25 miles from St. Louis.

But before Dennis Spellmann became president of Lindenwood, nearly 30 years ago , it was a different place.

With only 500 resident students, Lindenwood was a small college. The brick buildings and athletic complexes on the new side of campus had not been built yet. Instead it was an unkempt trailer park, roller skating rink and a bank along First Capitol.

Students ran the show at Lindenwood. Having alcohol on campus and visitation without limits. Cobbs Hall even ran a bar called Spanky’s Tap. The atmosphere was a small town feel – relaxed and friendly.

On the other hand, many dorms were unoccupied and falling apart. Butler Library’s collection was sparse and out of date.

The Eden of Lindenwood College was in trouble. Limited enrollment and significant debt almost pushed the institution to shut its doors. That is, until Dennis Spellman got behind the wheel.

Spellmann has been credited with saving the school. But at what cost? On this podcast – over a decade since he died – we’ll talk to former students, faculty, and staff who were here during his tenure. We’ll tell the story of the man behind Lindenwood’s dramatic transformation, what he did, and how he is remembered.

To set the tone of pre-Spellmann, these are excerpts from a sobering letter in 1986 to Bob Hyland, then the president of Lindenwood College’s board of directors, from former professor Bill Symes.

“Someone has said a good leader does the ‘right things’ and a good manager ‘does things right.’ You have deficiencies in both areas.” “But I think you may still have time to pull this out of the fire, if you begin immediately to do some of the things that should have been done some time ago.”

Obviously, it turned out that Lindenwood was able to “pull itself out of the fire”. But back then, things were not so certain. Lindenwood, a 160-year-old college with Presbyterian roots, was in danger of closing, and desperate to solve its chronic financial problems.

Dr. Christie Rodgers, who works in the Student and Academic Support Services office, graduated from Lindenwood in 1987.

Dr. Christie Rodgers: The school was really struggling financially. There were also very few students on campus. You could walk from Parker over to Roemer, during prime time class time, and really not even see a soul. There were a lot of buildings that didn’t have anyone living in them.

KD:The numbers were not adding up, leaving employees unsure of whether the school would stay in business.

In 1986, Rich Reighard, now a communications professor, came to Lindenwood as a student, and later worked as director of the KCLC radio station, which is the radio station at Lindenwood.

Professor Richard Reighard: We all heard the rumors, and for those of us who were getting a paycheck from Lindenwood, we cashed them quickly, because there was serious concern that they would bounce.

KD:It looked like Lindenwood was a goner, just another private liberal arts institution that had to shut its doors.

Professor Grant Hargate: I think one semester out of 35 years, I didn’t work because they weren’t sure if they were going to keep the college open.

KD:That’s Grant Hargate, a studio art professor since 1983

GH: There were all kinds of rumors bunching around. And I you know, I was a little disappointed because I just got the job. My dream job was to teach college. I got the job when I was 26.

KD: It wasn’t just a rumor that Lindenwood considered throwing in the towel – more than once. Having financial problems since the 1960s, the board considered closing the school as early as 1973. In the 1980s, Lindenwood tried to sell the land to other institutions, most famously the St. Charles Community College – for just a buck. These plans never materialized, though. But Lindenwood was in dire straits under Spellmann’s predecessor, Dr. James Spainhower.

Spainhower decreased Lindenwood’s debt, but even he – the former Missouri state treasurer could not solve the college’s serious woes.

When Spainhower resigned in the middle of the school year, the board considered selling the college. This proposal failed by just one vote, and administrator Dr. Dan Keck became interim president.

This set the stage for Spellmann. He had been connected with Lindenwood for years as a consultant, and was even a candidate for president of Lindenwood College before Spainhower was hired in 1982.

So, Lindenwood hired him as a consultant again, and quickly, he was running the show – in his style.

Spellmann had a reputation for making tough financial decisions at other struggling colleges, including turning around Maryville College when Hyland was board chairman there. But, his history involved what some considered questionable methods.

He worked at several Historically Black Colleges, and other schools which – like Lindenwood College – were in trouble.

But in 1990, two Missouri colleges where Spellmann worked were audited by the Department of Education. The government accused Missouri Valley College, where Spellmann was still executive vice president, of 36 legal violations, which included the school cashing unendorsed work-study checks, and a student receiving a Pell Grant for a semester he did not attend school.

According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, Spellmann took advantage of loose federal student aid laws to bring “high school dropouts, recovering drug addicts, and unwed mothers” to Missouri Valley College and Tarkio College – and in doing so, brought millions and millions of federal student aid money to the schools’ pockets Tarkio had the nation’s highest student loan default rate: 79% in 1986, when Spellmann left.

It went bankrupt five years later.

Spellmann told the Wall Street Journal, “I didn’t invent these grants. If the government didn’t want these people eligible, they could change the rules.”

He also said he was unfairly persecuted and defended himself by saying he was only helping the poor. In one press release, he said, “What the Department of Education is saying, in essence, is that we should be keeping them out rather than helping them out.”

Spellmann survived the negative press without being found guilty of anything, and some saw him as a hero with a gift for saving dying schools.

Before Spellmann was at Lindenwood College for long, student aid laws were tightened. However, he took in as many students as possible, starting a dramatic recovery which garnered national attention.

Richard Reighard: There was a whole lot of folks who were wondering whether the Lindenwood College era was gone forever, and it would’ve been, except for President Spellmann.

KD: According to a colorful 2000 profile of Spellmann in the Riverfront Times, he came from a farming family in East Texas.

A veteran of the United States Marine Corps, he had a Southern drawl, a strong work ethic, and a master’s in public administration from UT-Austin.

“Well, you need food, and you need food for thought, and I think sometimes they go together.”

That was Dennis C. Spellmann himself, in an NPR interview from 2002.

Matt Hampton: Was he kind of an imposing guy personally?

KD: That’s our co-host and producer, Matt Hampton, talking with Chad Briesacher, the current KCLC director who was a student in the Spellmann Era.

Professor Chad Briesacher: Yeah, because he was kind of a big guy. I was certainly scared to approach him. He was standing there in the cafeteria almost every dinner my freshman year.

KD: Part of the reason students were intimidated was that Spellmann was known for the strict rules he enforced – taking away the carefree culture Lindenwood College had in the 70s and 80s. Campus visitation was revoked. Work loads for professors increased. But sometimes people saw a happy, charismatic man. In other words…

Richard Reighard: Well, he was complex.

KD: Professor Reighard said Spellmann had a good side and a bad side – causing the staff to look out for each other when Spellmann was in a bad mood.

RR: He had a tendency to be Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, if you understand that kind of idea. Some of the folks in the president’s wing up in Roemer, they took pretty good care of us, meaning someone would surreptitiously pick up a phone call and say, “You got a meeting today with the resident? Cancel it. It’s a red pill day.” He had red pill and green pill days. If it was a red pill day, you didn’t want to go anywhere near the president, because he was just raging and pounding his fist on the desk and cursing and looking for someone who did something wrong that he could yell at. And if it was a green pill day and he’s leaning back in his chair, carrying on or whatever, that was good. All the deans and all the program chairs and anybody who had to deal with the president was like “What kind of mood is he in today?” because if he was in a bad mood, that was bad.

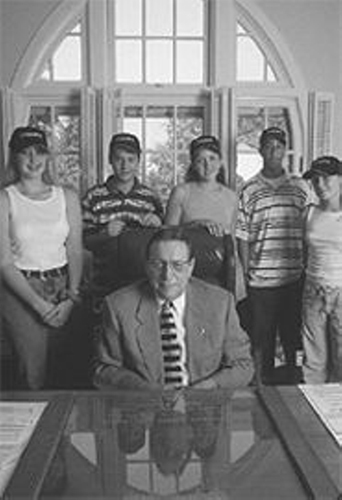

Photo from the Riverfront Times

MH: Spellmann had a sense of humor, but his temper could flare up any minute. Glen Cerny, who was the faculty athletic representative, experienced this quite often.

Glen Cerny: We laughed about a lot of this stuff as soon as it was over too. We knew that it was a tempest, and it was gonna blow over and – I found my humor kept me there as long as it did

MH: I hear that he kind of had a strange sense of humor about this. He would go yell at somebody, and then he would laugh about it afterwards.

GC: Oh, absolutely. Yeah the person would leave and he’d laugh and he’d go “wanna see me do that again?” No, I don’t, what you did was just humiliating.

MH: Mira Ezvan has been teaching in the school of business since 1984.

Dr. Mira Ezvan: He just was a very stubborn, you know, person. Once he made up his mind about something, that’s what he wanted, and he was not willing to negotiate.

MH: One example of this was when he insisted on having graduation outside by the gazebo like always – in spite of what the weatherman said.

ME: The forecast called for torrential rain. But of course, Spellmann believed that God will not rain on him. So the graduation was still scheduled outside. And then it was like 10 minutes into the ceremony when the downpour started, and everyone got soaking wet.

MH: From then on, graduation was held indoors, she said.

KD: Dr. Michael Mason was Chaplain during most of the Spellmann years. He said Spellmann’s leadership turned many people off, but his tyrannical reputation was more bark than bite. And yet it was true that Spellmann liked to make it clear who was boss.

The Rev. Dr. Michael Mason: Like a drill sergeant or Marine sergeant, if you could deal with it, it was great. If you couldn’t deal with it, a lot of people left. I had a great deal of respect for him, when he would yell, I knew he wasn’t yelling at me. He was yelling about the situation. And he taught me not to go into his office without having done my homework because I better have my ducks in a row before I presented them to him. If you can live with that kind of leadership, that’s great.

MH: So that’s what professors did – they lived with his leadership methods – because after all, Spellmann was the one who saved Lindenwood – right? But why did he act this way? Did he just get angry easily? Perhaps as a former captain in the marines, he thought this was the strong leadership that was needed to save a school in a battle to survive.

KD: Dr. Rodgers said Spellmann had a tough love side for some of his employees.

Christie Rodgers: I believe he had the business, Marine side of him, and then he also had the very caring, kind side of him. I have seen him scream and curse and pound his fist on the desk, which was quite scary. Never at me except for one time. He expected big things, but if you were talking with him outside of this environment, you wouldn’t know that he had an iron fist.

Penny Bryant: I’ll tell you. I’ll give you an example. I’ll ever forget this. My ex-husband and I were dorm parents in Parker Hall

MH: That’s Penny Bryant, director of SASS, who also worked under Spellmann.

PB: I was working in the development office, and he pulled me into his office and said – he was very stern to tell me that my husband at the time was, to put it nicely, a terrible person, and that he reminded him of his daughter’s ex-husband, and he went on and on, and I’m sitting there thinking, “Well, this man has a lot of nerve to tell me this.” But you know what? He was right.

CR: Trying to watch out for you.

PB: Yeah, he was trying to watch out for me, in the nicest way he could, because I remember walking back to the dorm thinking “That was really weird, and how could he say that,” but then it turns out that he was correct, and he took care of me afterwards. So I will never forget that.

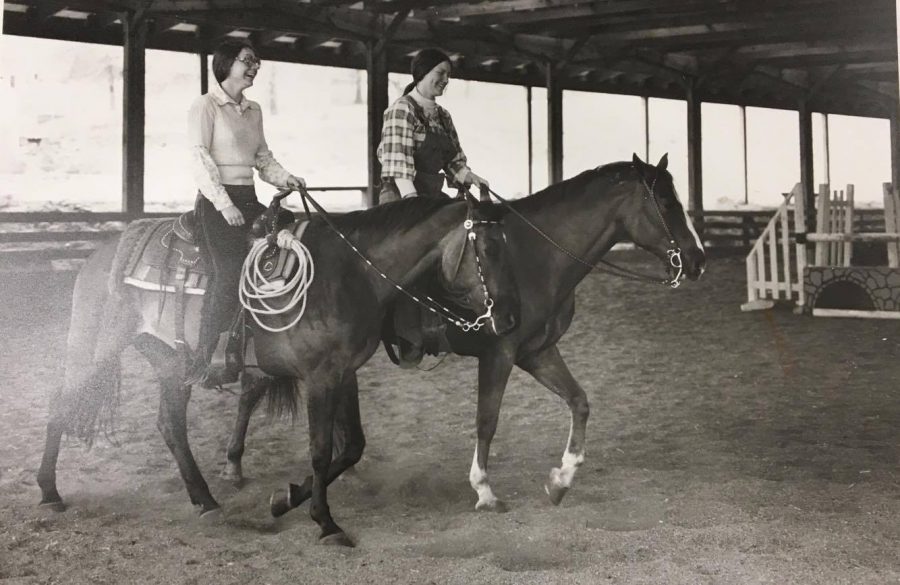

Image from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

KD: So, who was Spellmann? He was a complex person. His way of doing things was polarizing, but his success at saving Lindenwood College from extinction outweighed the negatives in the minds of many.

To hear more about Spellmann’s business mentality that dramatically changed the landscape of Lindenwood – you’ll have to tune in to the next episode in the series. For now know that Spellmann’s way of operating still affects the university to this day.

MH: Plus: pork, the other tuition payment.