MATT HAMPTON | Sports Editor

The cemetery on Lindenwood’s campus, which sits on a hill overlooking a pond across the road from Hunter Stadium, has an almost 200-year history.

Photo from “Reminiscences of Lindenwood College”.

The land where the cemetery sits was owned by Lindenwood’s founders, who gave it to the First Presbyterian Church of St. Charles in 1853. According to the Lindenwood Colleges Bulletin, originally there were plans to create a more elaborate burial ground, but they went unrealized. The college bought the cemetery back from the church in 1916.

This summer, signs were put up commemorating 29 individuals buried there. But since then, University Archivist Paul Huffman discovered the names of more people who were laid to rest on campus but do not have gravestones.

In total, Sibley Cemetery is known to contain 34 people and three dogs. At least 12 of the humans died before turning 18, and all but four graves date from the 19th century.

The Watson obelisk

The oldest grave in the cemetery is marked by an obelisk put in place by William Watson and Judge Samuel S. Watson, the first president of the Linden Wood Board of Directors.

Beneath it, three members of the Watson family were buried in the 1820s: Martha Watson (1770-1824) and Archibald Watson (1761-1826) and their son John W. Watson (1806-1821).

Rufus Easton

[masterslider id=”56″]

In 1834, Rufus Easton, the father of Lindenwood’s founder and first president, Mary Sibley, died of cholera and was buried in the cemetery.

The Easton family moved to Missouri from upstate New York when Mary was a child. Thomas Jefferson appointed Easton the first postmaster for the city of St. Louis and a territorial judge.

“Family lore was that he also served a purpose to spy on [Territorial Governor James Wilkinson], who was thought to be conspiring with Aaron Burr to divide the United States into two different countries,” Huffman said.

During his life, Easton was also the second attorney general of Missouri and founded Alton, Illinois, which he named for his son.

Woodville Bates

The son of Frederick Bates, Missouri’s second governor, died in 1840 at age 16. Woodville was the first of multiple relatives of the governor to be laid to rest at Linden Wood.

Gov. Bates lived at what is now Faust Park in Chesterfield, Missouri, and much of his family is buried there.

The Andersons

[masterslider id=”57″]

Mary Sibley’s nephew, Thomas L. Anderson Jr., died as a baby in 1840, and his mother, Rusella Easton Anderson died of tuberculosis later that year. They are buried next to each other in the cemetery.

Abial Alby Easton

Mary Sibley’s mother, Abial Alby Smith Easton, died in 1849 and was buried next to her husband, Rufus Easton. Little is known about her life except that she hated the Presbyterian religion Mary joined, according to Mary’s diary.

Washington

One of the Sibleys’ slaves named Washington died of cholera in April 1849. He was buried at the Linden Wood cemetery but has no known gravestone.

Elizabeth L. Easton

In 1850, Elizabeth L. Easton died giving birth in Santa Fe, New Mexico at age 23. She was Mary Sibley’s sister-in-law, and her widower, General Langdon Easton, had Mary raise their three children at Linden Wood.

Other unmarked graves

Catharine Johns, the wife of Board Member John Jay Johns, died in 1846.

Huffman said that Matilda Alderson died in March 1847, possibly during the birth of her infant daughter, who died later that year. She was the wife of Board Member B.A. Alderson, who went on to lose four more children in the next year: Eunice (3), George (4), Martha (8), and Mary (6). They are buried together at Linden Wood, but have no tombstone today.

William Douglass, a member of the Sibleys’ church, died in December 1851.

One month later, a 4-month-old daughter of Andrew King also died. Little else is known about them.

Lucy Harrington

Teacher Lucy Brigham Harrington came to Lindenwood in 1852 from Massachussets before dying of “dropsy of the chest” at age 26 the next fall, according to the diary of John Jay Johns, who was President of the Board of Directors.

Betsy Dick

Huffman said Betsy Ann Dick was not listed on the current graveyard sign because he suspected her headstone was stolen from another cemetery.

“The tombstone was broken, and it was just kind of lying up against the fence,” Huffman said. “I found it was kind of at a period where people were going into graveyards and breaking tombstones, so I just thought maybe it was like a student prank.”

In reality, Dick was the wife of a Linden Wood board member, and was buried at the college in 1855.

Neville Christy

Neville Christy was a student at Lindenwood in 1857. According to a letter from her younger sister in a book compiled by a Lindenwood dean in 1920, Christy’s health forced her to leave before graduating. When she died a few years later, she was buried in the cemetery because of her love for Lindenwood, but has no gravestone.

The Waltons

[masterslider id=”58″]

Everett Walton, the 1-year-old grandson of Frederick Bates, was buried in 1858. Everett’s sister, Nannie Fleming Walton, died in 1859 at age 13. Their father, Robert A. Walton was buried in 1867, and Elmer Walton, his grandson, died in 1864 at age 2.

Willie Schenck

Photo by Matt Hampton.

The stepson of the Rev. Addison V. C. Schenck, Lindenwood’s second president, died of typhoid in 1858. After Willie died, the president was said to visit his grave every evening.

Josiah Cary

The 77-year old father-in-law of President Schenck died in 1861.

“Grandpa Cary” as students called him, lived with Schenck and lead daily church services at Lindenwood.

George Sibley

[masterslider id=”59″]

Maj. George Champlin Sibley, an explorer and husband of Mary Sibley, Lindenwood’s first president, died in 1863.

Over his career, he went on several excursions throughout the West, forming relations with the Indian tribes. In 1808, he was assigned to help create Fort Osage, which now lies east of Kansas City.

Before coming to St. Charles, Maj. Sibley was struck by lightning during an expedition to survey the Santa Fe Trail. This accident caused him health problems for the rest of his life, Huffman said.

After the expedition, he moved with his wife to St. Charles, where they founded Lindenwood.

Though he was bedridden and frail in his later years, Maj. Sibley survived to the age of 80.

James Walker

Photo by Matt Hampton.

In 1868, James S. Walker was buried in the Lindenwood cemetery. Little is known about him, and it is unclear from his tombstone at what age he died.

Mary B. Easton and children

A monument in the upper fenced area marks the grave of Mary Sibley’s sister-in-law, niece and nephew.

Louisa Gamble Easton was born in 1850 and died in 1851. In 1875, Mary B. Easton, the wife of Henry Clay Easton, died and was buried with her daughter. Five years later, their other child, named after his grandfather, Rufus Easton, also died.

Mary Easton Sibley

[masterslider id=”60″]

The founder and first president of Lindenwood was buried in 1878 next to her husband.

The first of 11 children, Mary Easton was born in upstate New York in 1800 and came to Missouri at age three. At age 15, she married the 33-year-old George Sibley at Fort Osage.

The Sibleys moved to St. Charles in 1827 and founded Linden Wood. Mary served as president until she retired in 1856 and deeded the college to the Presbyterian Church.

In her 70s, Sibley converted to the Second Adventist sect, and traveled to California in preparation for a missionary trip to Japan. However, she fell ill and returned to Lindenwood, where she died.

President Roemer’s dogs

[masterslider id=”61″]

After Mary Sibley died, the next burials in the cemetery were three of the Rev. John Roemer’s pets.

The president’s most well-known dog was Kurt von Lindenholz, a German Shepherd who died in 1934.

Huffman said Kurt was known for his intelligence and would walk students to their homes around town and back to campus alone. He was so popular, it is said, that a group of students gathered to sing hymns outside the room where he died when he passed away at age 13.

Roemer’s Pomeranian, Lin, and Bobbie, another German Shepherd he owned, were also buried in Sibley Cemetery.

Norma Jean Fields

Photo by Matt Hampton.

The last person buried on campus was Norma Jean Fields, a beloved professor of English and communications for over three decades.

She passed away in her sleep on April 2, 1998, and her funeral was held at the Lindenwood University Cultural Center.

The daughter of a West Virginia coal miner, Fields was born in 1932. She came to Lindenwood in 1965 from Ohio State University, where she earned a master’s degree and taught.

In an eulogy he gave, President Dennis Spellmann praised Fields’ unpretentiousness and dedication to Lindenwood.

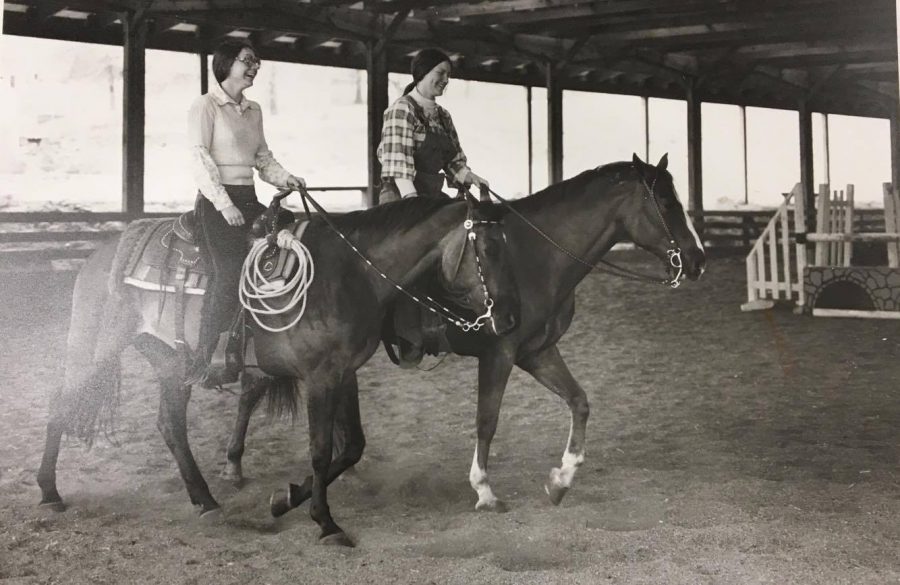

Photo from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

“Thousands of Lindenwood students have been blessed by Jean,” he said. “She has touched the lives of so many over the years.”

One of those students was Richard Reighard, now a Lindenwood mass communications professor. He said Fields was his mentor and hero, and she was “rather short, rather round, smoked like a dragon – that’s what killed her – and drank like a fish, never dressed up, sloppy as all get out, but one of the nicest people you will ever meet.”

Fields thrived on interacting with students, and once lived in Cobbs Hall with her freshman advisees, according to the February 1968 Lindenwood College Bulletin. Reighard said she also got along with her colleagues, and was too focused on teaching to get involved in office drama.

“She just kind of let the whole world roll past her and did her own thing; she was just this island of smoky, sloppy serenity in the middle of chaos, and that’s why we loved her; she was very unique,” he said.

Fields received the Emerson Electric Award for Excellence in Teaching and the Sears Award for Teaching. At Lindenwood, she taught a diverse range of material, from English literature to American tall tales to science fiction, and had a passion for history.

Photo from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

Fields studied cinema arts and worked on movie sets in California before coming to Lindenwood, where she started the film program in the basement of Butler Library in the days before VHS tapes. Reighard said he resurrected the program in her honor after she died.

Because of Fields’ connection to Lindenwood, it seemed natural for her to be buried on campus, Reighard said.

“Every once in a while when I’m back by the graveyard I’ll stop by and say hi,” he said. “She was probably the most beloved professor I ever saw here at Lindenwood during my 32 years or whatever I’ve been here.”

–

Lindenwood, founded as the oldest women’s college west of the Mississippi, has had a rich and unique past. This is the seventh article of Lindenwood Then and Now, a series about the school’s history. The previous installment, “campus buildings that are now history,” told the story of some of the many now-defunct campus buildings from Lindenwood’s past.