MATT HAMPTON | Sports Editor

This semester marks the 50th anniversary of the first male students to live on Lindenwood’s campus.

Fall 2018 saw the first co-ed dorms at Lindenwood, which today serves nearly as many men as women. But in fall 1968 when the first men officially attended, it sparked both controversy and social change at what was traditionally a women’s school.

Women only (1827-1968)

Mary Easton Sibley founded the Linden Wood School for Girls in 1827 to educate young women, and the college served that purpose for over a century.

University archivist Paul Huffman said an endowment created with $3.5 million from the Butler family in the 1910s allowed Lindenwood College to transform into a four-year school from a two-year college. After this, the college marketed itself as a finishing school for upper-middle class families to send their daughters to, calling itself “Wellesley of the West,” after an elite women’s school in Massachusetts.

There was a greater focus on teaching women how to manage a home in the decades before men came to study at Lindenwood. In the 1950s, Lindenwood had a program called home management, where women gained hands-on housekeeping experience in a model house, but it was disbanded in 1967.

Changing views about women and the increasing demand for science education during the Cold War lead Lindenwood to erect the Young Hall of Science in 1966 and encourage more students to enter science-related fields.

Huffman said the dominant philosophy at the time was that colleges should function in loco parentis, or as if they were students’ parents. Women at Lindenwood were no exception to the restrictive rules this doctrine placed on students.

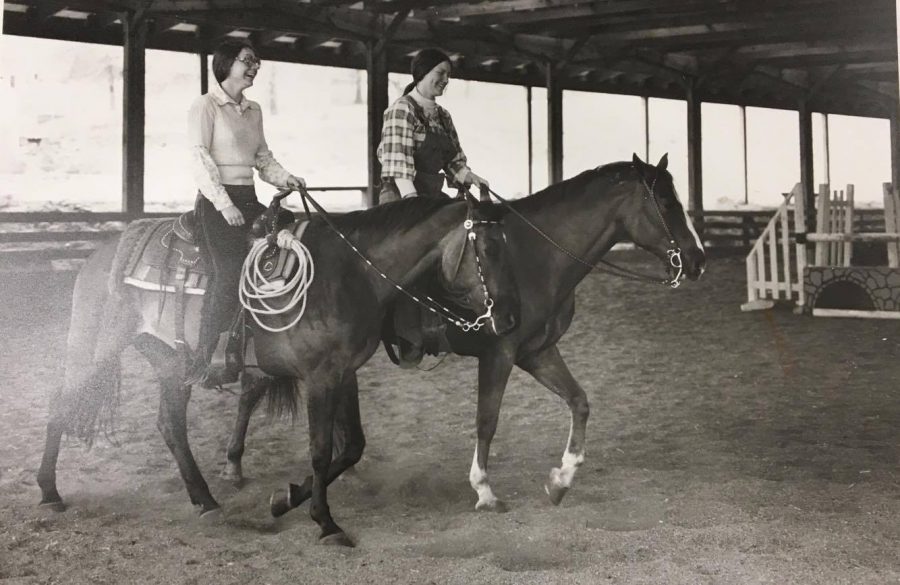

Photo courtesy of the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

The 1961-62 course catalog prohibited Lindenwood women from getting married without permission of their parents and the college. Huffman said in an email that this may have been because of incidents of professors marrying students.

Until 1970, dorms were supervised by house mothers, and residents required their permission to spend the night off campus. The 1969 student handbook stated that women could only have overnight guests in their room if they had a separate bed and did not stay more than three nights straight.

Aside from faculty and staff, the only men at Lindenwood before 1968 were admitted to build sets and play male parts in theater productions. Huffman said these men were allowed to take classes, but only a handful were enrolled each year.

But in the late ’60s, financial and enrollment troubles forced Lindenwood to seek a new approach to stay afloat.

“The administration at the time just started burning through the endowment, and they were having problems holding on to students past their sophomore year,” Huffman said. “After their sophomore year, they were transferring out to state colleges.”

Dr. John Anthony Brown, who became president of Lindenwood in 1966, considered bringing men to the college as a solution to the administration’s woes.

Lindenwood’s student newspaper, the Bark reported in May 1967 that the administration was considering a proposal for “a coordinate men’s college adjacent to the Lindenwood campus.”

A year later, Brown said the college was investigating “the male market” and there was a possibility between 12 and 20 men would be enrolled in the fall.

“Under no circumstances will we admit men who do not fulfill the same requirements as the students that are here,” the Bark quoted Brown saying.

According to the article, only plans for “a coordinate, not a co-educational” school were underway, “to maintain as much of Lindenwood’s individuality as possible.”

Battle of the Sexes (1968-1979)

When students came back to Lindenwood in the fall of 1968, a group of men known as the “Fabulous 15” had been admitted.

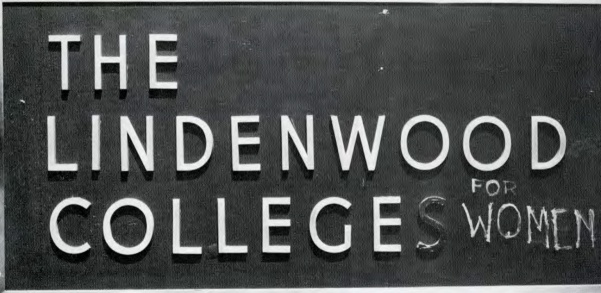

Brown created a separate college for men called Lindenwood College II. Huffman said this was done because of fear that if Lindenwood became officially co-ed, it would lose its charter, which granted it privileges usually reserved for state schools.

Male and female students at the Lindenwood Colleges had separate student governments, but they attended classes together and acted as one school for most practical purposes, Huffman said. Lindenwood II was disbanded in 1979 when the administration decided it was not a risk to the charter.

Photo from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

Admitting men angered some women, who protested and burned a straw dummy outside of Ayres Hall, the men’s dorm. Huffman said the effigy either represented Brown or the male students.

Some women were worried about introducing men onto the insular, conservative campus and were outraged Brown did not consult students, Huffman said.

“They liked the exclusivity of the college, and they thought as a women’s school, they don’t have to worry about competing with men, and they felt like there wouldn’t be the pressures of dates and stuff like that,” he said.

The fact that the rules were not as strictly policed for the men also angered Lindenwood women. Glen Cerny, who studied at Lindenwood’s KCLC radio station in the 1970s, said men were largely “unchaperoned” and free to ignore the rules.

In the years after its creation, Lindenwood ll’s enrollment grew. The 1969-1970 yearbook included 35 male students.

A Sept. 1969 article in the Ibis, then Lindenwood’s biweekly newspaper, quoted student Phil Davis saying sarcastically, “The tradition of having girls on campus is a very good tradition to continue for a long time.”

According to the article, some women welcomed the diversity and energy the men brought, but some thought the men were slovenly and rude.

“Go get a haircut and take a bath!” one woman said. “I know there are showers in Ayres; I used to live there. I was ashamed for my parents when they came. I am only too glad I don’t have classes with them.”

By the time Cerny came to campus from Wisconsin in the fall of 1970, the student body of at least 600 included about 100 men, enough for a second dorm. He said the men and women “blended wonderfully together very quickly,” and only “vestiges” remained of the traditions that were dominant a few years before, such as formal dress code.

Photo from the Mary E. Ambler Archives.

“I vaguely remember some white gloves, but to be honest with you[…] we were having a blast, and some of the girls from our class came in and said, ‘Gee, this is fun,’” Cerny said.

A provision in the 1968 student handbook stated, “Women students are encouraged to wear skirts and blouses to the dining room for the evening meal each day and to the noon meal on Sunday.” By 1969, the handbooks, which were printed separately for the two colleges, did not contain similar language about mealtime attire.

Cerny described the early Lindenwood men as smart but “hyperactive” and “immature.” He said their freedom not only allowed for fun but a lot of useful experience.

“When you look at the success that that group from the radio station had collectively, it’s because we lived and breathed it. We just took advantage of everything we could, and there was a lot to take advantage of because no one was watching us,” Cerny said.

–

Since Lindenwood’s foundation as a girls’ college when Missouri had been a state for less than a decade, the school has had a rich and unique history. This is the second article of Lindenwood Then and Now, a series about the history of Lindenwood. Last week’s installment, “Rooted in History,” showcased the history of three notable campus plants. Check back next week for more.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that Lindenwood II was disbanded in 1983. The correct date is 1979, but Lindenwood continued to be called “The Lindenwood Colleges” until 1983.