Lindenwood’s history with slavery is complicated

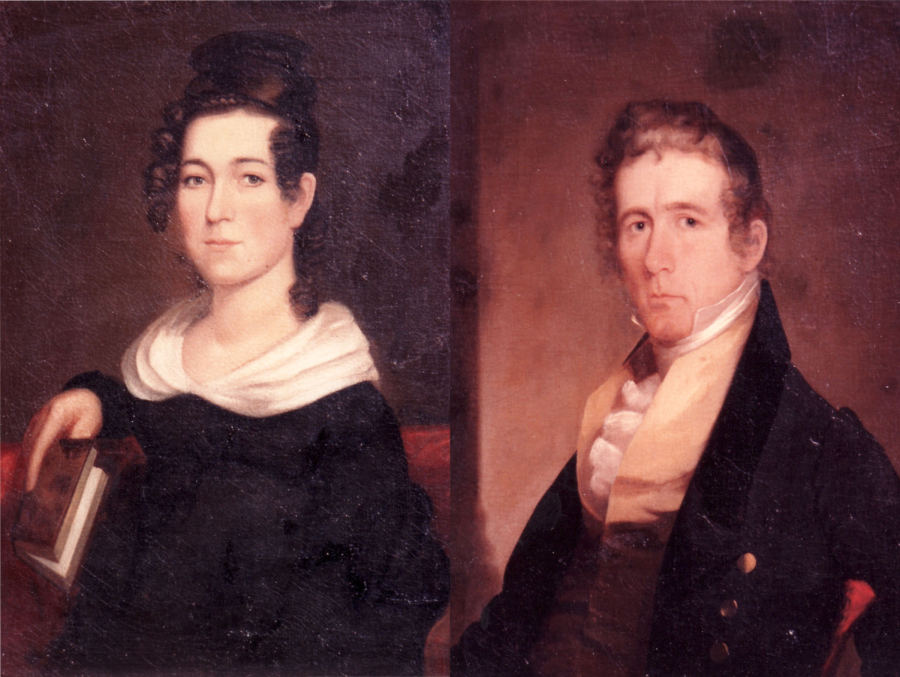

Photos of Mary (left) and George (right) Sibley, available in the Archives room on the first floor of the Larc.

May 2, 2023

Lindenwood University has a history with slavery.

Lindenwood’s founders owned slaves when they started Lindenwood in 1832, according to historical records.

“Our founder Mary Sibley and her husband George Sibley did own slaves before the civil war in the United States,” associate professor of religion Nichole Torbitzky said.

According to Lindenwood University’s website, the Sibleys moved from an area near Kansas City to Saint Charles in 1828. After a few years, Mary Sibley opened a girls’ school that eventually became Lindenwood University.

The website does not mention slavery but records have shown that George did own slaves. Mary was opposed to owning human beings and went so far as to create a school to try to educate enslaved children.

“The Sibleys, prior to coming to Lindenwood actually had quite a few slaves, and then when they became in debt they had to sell off a bunch of them,” Lindenwood Archivist Paul Huffman said, explaining that the couple had two slaves when they came to Saint Charles. “But by the 1840s I think the most slaves that were here at Lindenwood were six slaves.”

It was not uncommon for slaves to be used as collateral for loans in the 1830s. According to the Los Angeles Times, banks like Citizens’ Bank and Canal Bank of Louisiana “accepted approximately 13,000 slaves as collateral for loans between 1831 and 1865.”

Huffman said the Sibleys had to mortgage their belongings to raise money to pay the debt.

“They had to show what they had for collateral and they listed the people who were their slaves,” he said.

Torbitsky said there is evidence that Mary Sibley was against slavery, but it did not stop her husband from owning them.

“Mary Sibley, what we know from her writings, was very anti-slavery. But her husband owned them,” Torbitsky said. “As far as I know, and as far as the way the world worked when Lindenwood was being founded, the use of slaves’ unpaid labor was not uncommon.”

Mary created a school for enslaved children, but it was closed by slave owners not so long after she opened it.

Huffman said slave owners were scared of what could happen if the people they use as slaves were going to school.

“There were a lot of fears from slave owners that if they became educated they would rebel against slave owners,” Huffman said. “I guess the slave owners told her she couldn’t have the school anymore.”

The school being closed did not stop Mary. She decided to open a Sunday school for them.

“Her argument was a really good one, one that abolitionists used during the time, which was we want everyone to know Jesus Christ, we want everybody to be Christian, and the only way to do that is to be able to read the bible,” Torbitzky said.

“She believed that educating people, particularly people who don’t have or have limited access to education like women at the time, and like people who are enslaved, she believed that this would make the world a better place,” Torbitzky said. “She did what she could within a pretty horrific and evil system to try to make the world slightly better.”

Even though George owned slaves, the Sibleys were connected to a famous abolitionist of the time. Elijah Parish Lovejoy was a newspaper publisher who was killed for his anti-slavery beliefs in 1837.

“We know that she [Mary Sibley] supported a famous abolitionist, Lovejoy. He came to this area to preach, to encourage people to stop this practice. A group formed to attempt to kill him, and the Sibleys were integral in saving his life,” Torbitzky said. “To help him get away from this mob that wanted to kill him.”

Lovejoy had angered slave owners because he started an anti-slavery newspaper called the St. Louis Observer. According to Reporter Caryn Neumann in The First Amendment Encyclopedia, Lovejoy was not welcomed by St. Louis.

“Lovejoy believed that the exposure of slavery’s evils would lead to its abolition,” Neumann said. “As a pacifist, he did not encourage violence against slave owners, but rather sought to influence public opinion against slavery.”

The Sibleys were close to Lovejoy. When he started to get threatened in Missouri, the Sibleys helped him escape to Alton, Illinois, where he ended up getting killed by the pro-slavery forces.

“They helped [Lovejoy] to escape to Alton in 1837 after a mob attacked him at his mother-in-law’s home on Main Street in St. Charles,” reporter Linda Briggs-Harty said in the Saint Louis Magazine. “Lovejoy’s murder in Alton a month later helped start the Civil War.”

In recent years, many universities like Brown, Harvard, and Rutgers, have revealed their connections to slavery.

CBS News said that after its involvement with slavery was discovered, Harvard University committed $100 million to study and redress the institution’s historical ties to slavery.

The Daily Targum showed Rutgers’ failed attempt to acknowledge the relationship between its existence and enslaved labor by placing historical markers around several campuses.

The book Ebony & Ivy: race, slavery, and the troubled history of America’s universities by Craig Steven Wilder reveals that many institutions from the most prestigious to the smallest schools have shown a troubling past involving slavery.

The Sibleys owned slaves, but there is no evidence that they helped build Lindenwood.

“From the writings read from the founders, George and Mary Sibley, we know that slaves were here, but there is no evidence that they helped build any buildings here though,” Huffman said. “There is always potential that they helped, but there is no history that they did.”

Marcus Smith, an assistant professor of History at Lindenwood said that understanding history can be difficult.

“As faculty and students of the university that Mary Sibley founded, those of us in the History Program recognize the important legacy that the Sibleys have left us and feel that it is important to honor their achievements,” Smith said. “We do not, however, feel the need to whitewash or ignore the aspects of their lives that we find troubling, such as their ownership of slaves because we know well that historical characters, like all people, can be very complex.”

Smith said despite the complexity, it is important for students and faculty to learn about the school’s history.

“We hope that this kind of honest inquiry leads to a greater understanding of where we’ve come from as a university and a nation and where we are today,” Smith said.

Neighbor • May 9, 2023 at 10:50 am

Really informative article.