‘My escape from the real life;’ how one athlete traveled from Venezuela to US

Marialaura Villasana is originally from Valencia, Venezuela and came to the U.S. to swim with Lindenwood’s synchronized swimming team.

Photo from Marialaura Villasana

May 7, 2019

KAYLA DRAKE | Reporter

Just a few lanes away from her, in the open pool, 6-year-old Marialaura Villasana was mesmerized by dancers in the water.

“I was like ‘Oh my God, I want to do that,’” she said.

Villasana and her older brother started swimming because her mom did not know how.

“My mom at least wanted me to know how to swim,” she said.

She joined a synchronized swimming team that year. Her background in dance and swimming ensured she could do the splits and stay afloat.

Little did her mom know, her daughter would go on to compete for seven years with the Venezuelan National Synchronized Swimming Team. This talent was her daughter’s ticket out of a country with a corrupt government and declining economy.

“It’s my escape from the real life,” Villasana said.

This season was Villasana’s last as a team member, as she is on schedule to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Lindenwood University in December 2019.

Her ticket

In 2008, a Canadian coach, Genevieve Higgs, came to train Villasana’s select team in Valencia, Venezuela.

“She was the one that gave me everything I needed to succeed,” Villasana said.

Immediately the intensity in the pool amplified. Practice was extended from two to six hours. The coach intended to mold champions.

“She was super strict and back home we are not,” Villasana said. “We are not punctual at all. A totally different culture. And she was on top of everyone. You have to be here at 3 o’clock not 3:01.”

Villasana also spent extensive time outside of the pool doing gymnastics and lifting weights.

In 2008, Villasana made the junior national team at 11 years old.

She competed on the team until 2016, when she was 18 years old.

“At that point you play against the big ones – like Russia and China,” Villasana said. “For the soccer players it’s like playing against Messi.”

Life in Venezuela

In 2014 Villasana was selected for a duet in the junior world championship. If she performed well, she would garner the attention of national coaches.

Villasana practiced with her partner and rehearsed the four-minute routine for eight months.

Three weeks before the competition her coaches said they didn’t have the money to fly the girls to Finland for the competition. Villasana’s family didn’t have the money to buy the ticket in time. Neither did her partner’s family.

“That was a hit in the face,” Villasana said. “After all that work, boom, you’re not going.”

After that, Villasana gave up on her dreams of pursuing the Olympics.

“In this country, you can’t,” she said.

There is no Olympic synchronized swimming team in Venezuela. Now, four years after soaring inflation and rising poverty in Venezuela, she is witnessing a domino effect.

“The pools are getting bad,” she said.”They are closing the pools because there is no chlorine.”

Then coaches don’t get paid, and they move back home or search for other jobs. Villasana said the decline of synchronized swimming is not an isolated situation. It is happening to all sports.

“Before when I was a child we had 100 athletes in our competitions, now there are barely 30,” she said.

Villasana said it makes her sad to see all of the opportunities in the U.S. for synchronized swimming and the money invested into gear and sponsorships.

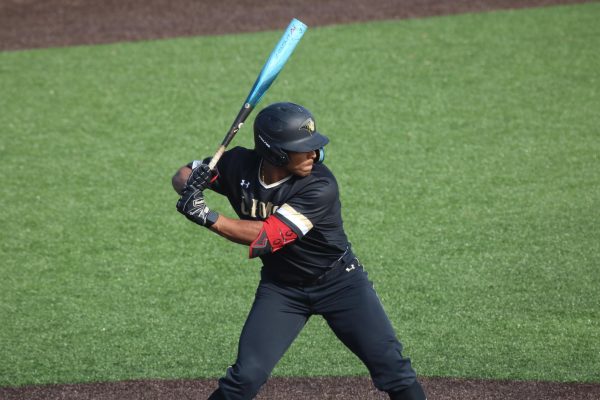

Photo from Lindenwood athletics.

“Back home it’s just impossible. People are looking for food,” she said. “You’re not going to ask for a bag.”

Coming to America

A friend from the Venezuelan national team who was a student at Lindenwood University told Villasana about its synchronized swimming team.

Villasana had already met Lindenwood’s coaches at world championships in 2015.

For several reasons, Villasana saw Lindenwood as a good fit and a chance to leave Venezuela. It was cheap, Olympic athletes were on the team and she could save money.

But her decision boiled down to one reason.

“Quality of life was the first thing,” she said. “Just walking on the streets without being scared.”

So Villasana same to the United States on a synchronized swimming scholarship at Lindenwood.

“My freshman year I was looking up to people from Russia, Spain, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Columbia,” she said. “You get to learn so much from everyone – techniques and culture.”

Now it’s 2019. Villasana was the team captain, a leader and an example for the freshmen this season.

“She’s like a big sister,” freshman Lindsey Papper said.

This year the team finished third overall in nationals. Villasana competed in the individual, duet and team routines, and scored high enough points on her technique to help the team place.

Photo by Kayla Drake

Making sacrifices

Even though her sport has given her an education, Villasana has made sacrifices to continually pursue it.

“At the beginning [of coming to Lindenwood] I couldn’t even speak English,” she said.

After four years Villasana has learned the English language and matured from a girl into a woman. She hasn’t been back to Venezuela since 2017.

“I want to see my dogs,” she said. “I want to be in my house. But at the same time, it’s like I’m better here.”

After graduation, Villasana plans to do Optional Practical Training, a year period the U.S. government gives international students after college to find a job.

But going home is not an option.

“If you talk to many Venezuelans they tell you ‘I’d die to go there,’ but at the same time if I go [home] it’s not going to be the same,” she said. “If I go I’m not going to have power or water in the shower.”

Villasana’s strength has impacted her teammates.

“She makes me sad sometimes when she says I haven’t seen my mom or dad in years,” teammate, Addison Cupples said.

This past winter break Villasana’s family was able to visit her in Miami for the first time in two years. Now, Villasana and her brother, who lives in Miami, are saving up money to buy her parents plane tickets to see her graduation in December.

“You see people complaining here about stuff, and I’m like you don’t know anything,” she said.

Villasana is a community adviser in Pfremmer Hall, a job that allows her to pay for her tuition and send money home sometimes.

“Even $50, [my parents] can survive,” she said. “It’s not that much, but for them it is.”

The high inflation rates render the Bolívar, the Venezuelan currency, poor. Currently $50 is worth 500 Bolívar.

Villasana is considering either pursuing a job in accounting or coaching.

“I have a lot of friends who are coaching right now and they are safe for that,” she said.

Once again synchronized swimming could be Villasana’s ticket – but this time it is to stay in the U.S.

Currently Venezuelan citizens are fleeing to other countries, like Ecuador and Spain. Villasana said she’s experienced discrimination because media in those countries will accuse Venezuelans of stealing local jobs.

But even though Venezuela is in disrepair, Villasana still has hope for her home.

“I’m not ashamed to say that I’m Venezuelan. I’m actually proud.”

Photo by Kayla Drake